The New Hollywood of the 1970s is generally regarded as the greatest artistic period in US filmmaking history, and the decade’s impeccable cinematic offerings seemed to permeate throughout all genres, be it gangster (The Godfather), romance (Annie Hall) and even horror (The Exorcist). The western, what had once been the staple of the US film industry, even received a revisionist make-over, with the likes of Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller and this 1972 remarkable achievement from director Sydney Pollack. Jeremiah Johnson is said to be the favourite amongst lead Robert Redford’s own large and illustrious body of work. It’s easy to see why.

The New Hollywood of the 1970s is generally regarded as the greatest artistic period in US filmmaking history, and the decade’s impeccable cinematic offerings seemed to permeate throughout all genres, be it gangster (The Godfather), romance (Annie Hall) and even horror (The Exorcist). The western, what had once been the staple of the US film industry, even received a revisionist make-over, with the likes of Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller and this 1972 remarkable achievement from director Sydney Pollack. Jeremiah Johnson is said to be the favourite amongst lead Robert Redford’s own large and illustrious body of work. It’s easy to see why.

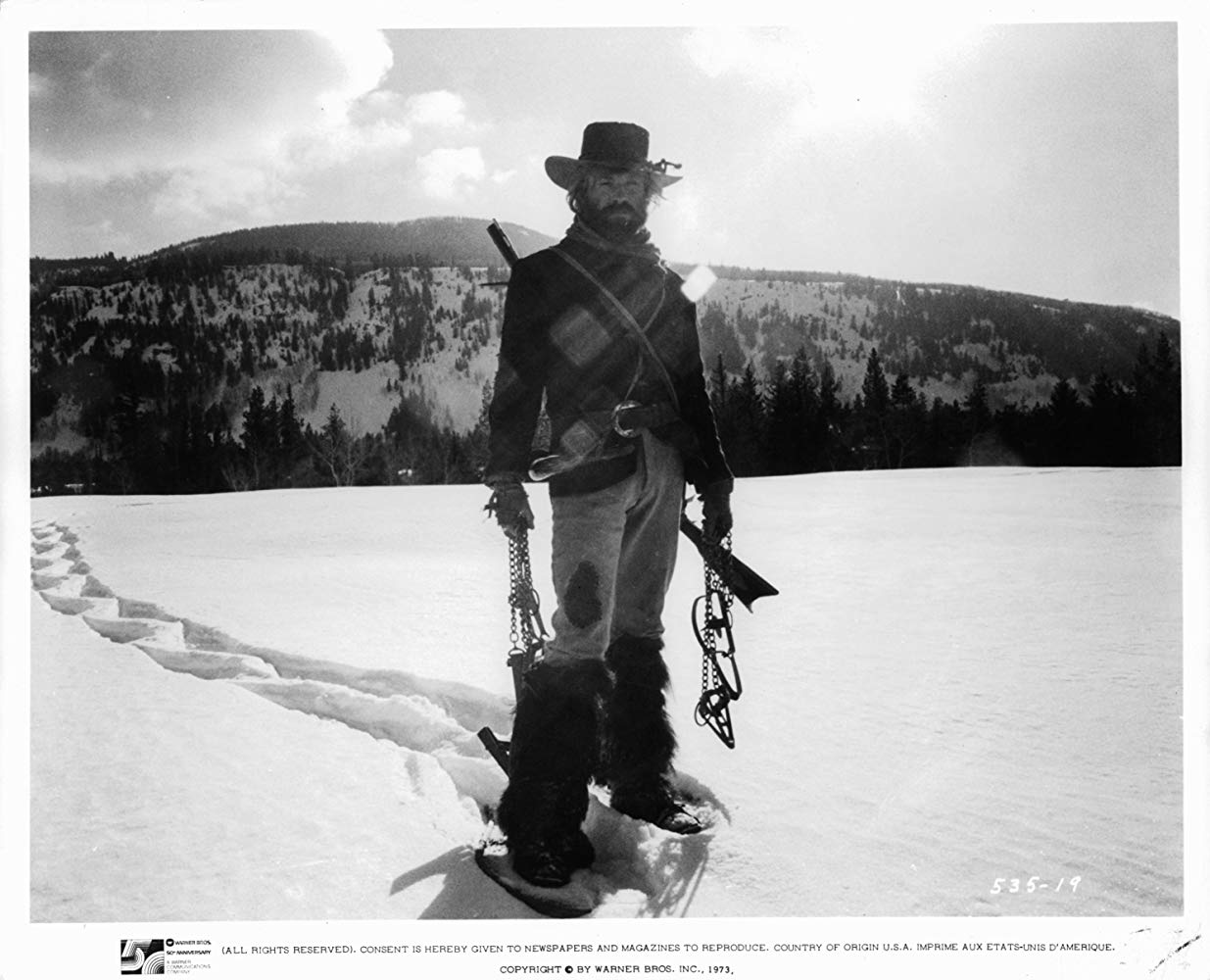

The first of several collaborations between the director and his star, like his role as a bookish low level CIA analyst in their later and equally memorable Three Days of the Condor, when you hear the character description of ‘rugged frontiersman’ Redford probably isn’t the first actor you would think of. In fact, both Lee Marvin and Clint Eastwood – two seasoned actors more than comfortable in this kind of world – were initially considered. Like Condor, Pollack’s directorial skills must be attributed to the grounded and gritty performance he’s able to coax out of the matinee idol, here buried under a suitably bushy facial hair.

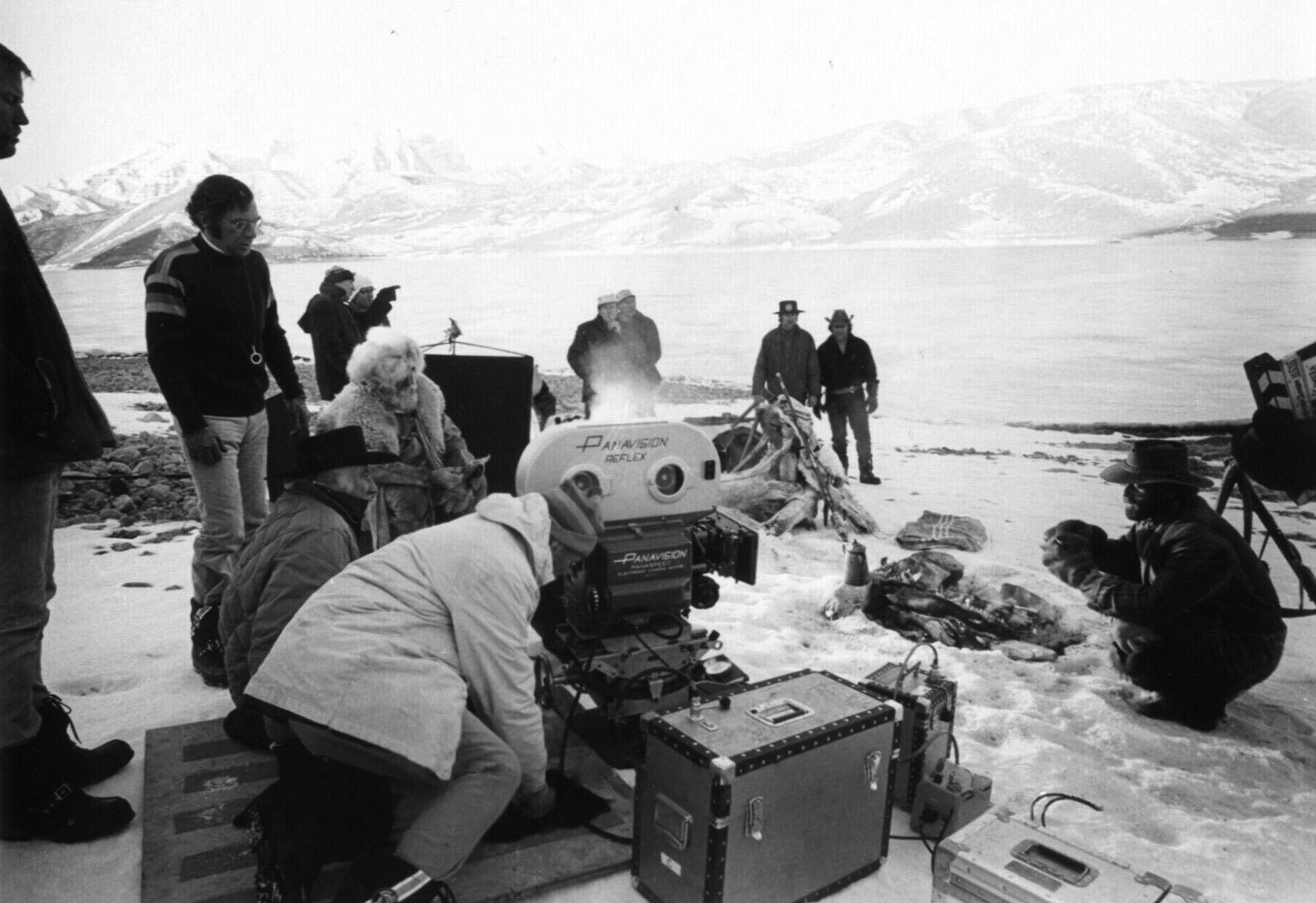

Redford’s Johnson – a former solder now trying his hand at trapping – is first seen traversing some particularly cold and unforgiving land. From there on, the character’s arc is really something to behold. His shift from novice (he’s mentored by a fellow mountain man early on) to surrogate patriarch, and then finally a bloodthirsty killer seeking retribution as the film switches to a brutal revenge flick, is rendered entirely believable through Redford’s committed turn. The series of montages which see Johnson traipsing around a whole series of stunning vistas, accompanied by modern anachronistic folk ditties, recalls the journey of the two central characters in Tarantino’s Django Unchained.

Like that film, Jeremiah Johnson doesn’t flinch with it comes to the portrayal of screen violence, some of these grizzly moments really knocking you for six. The film’s most haunting images are when Johnson discovers the frozen corpse of a famed hunter – his ghoulish figure bolt upright and perfectly preserved in the chilly surroundings – who has bequeathed his gun to whoever finds him. The other is the aftermath of the killing of two young white children, who have been mercilessly scalped by the Blackfoot Native American tribe, as their mother wanders around in the distance, tottering on the edge of insanity.

It may come of little surprise to those versed in that period of filmmaking that Jeremiah Johnson was written by the now legendary director/scribe John Milius, his handprints particularly apparent in those aforementioned scenes. Milius’ work here, alongside the sterling efforts of the director/star powerhouse make for an unforgettable and indelible slice of American folklore, which remains a superior and altogether more devastating critique of white colonialism than the similarly-styled The Revenant.

- Why To Live and Die in L.A. Is a Much Better Movie Than You Remember

- Why Highlander Is a Much Better Movie Than You Remember

- Why St. Elmo’s Fire Is a Much Better Movie Than You Remember

- Why Three O’Clock High Is a Much Better Movie Than You Remember

- Why Parenthood Is a Much Better Movie Than You Remember

- Why Lucas Is a Much Better Movie Than You Remember

Leave a Comment