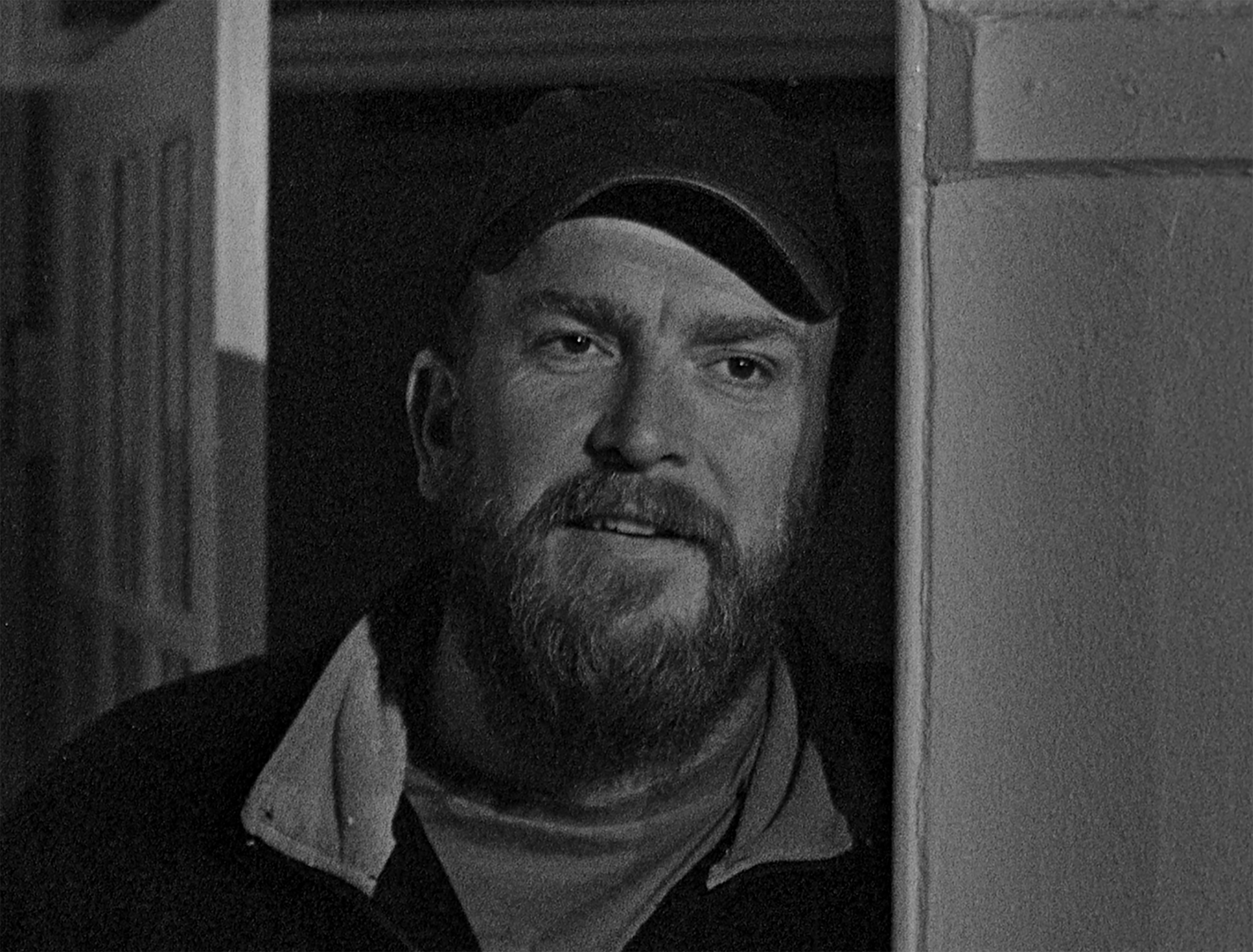

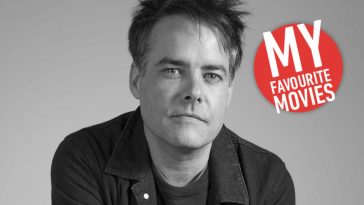

You only need to cast your eye over last year’s ‘best of 2019’ lists to get a sense for how received fishing drama Bait was. It has since been nominated for two BAFTAs and in the wake of this much deserved news, we had the pleasure of speaking to its creator, the talented director Mark Jenkin. We ask how it felt when he found out about the multiple nominations, and just his overall reaction to the film’s universal praise. He also comments on the film’s relationship with class conflict, and why he believes the movie to be a film about Brexit.

Firstly, huge congratulations on the BAFTA nominations. How did that feel, and where were you when you found out?

I was at home, I got at 7.30am to listen. I’d been told by so many people that we should get nominated, so I think I was a bit confused about whether we would or not, because the word ‘should’ is pretty vague. I hadn’t thought about it too much, but then when the nominations came through, in some ways it was amazing, and in others I was quite relieved after everyone had hyped the film up so much. The Best British Film one is the amazing one really, that took a little while to sink in when you look at what else in on the list, and what has been left off the list as well.

The film is brilliant and deserving of all this recognition, but is it still a surprise to you that it’s getting these sort of reactions? At one point it was idea in your head, now it’s multi-BAFTA nominated, Mark Kermode giving it five stars.

Yeah, I started working on the film in 1999, that’s when I first came up with the idea, even if I haven’t been working on it solidly since then, it has been in my head, a project I’ve wanted to do. It has changed a huge amount along the way, originally it was going to be a found footage film, so it couldn’t really be any different than the original idea I had. So it has been kinda slow, and then suddenly all these things have happened. Since Berlin it has been pretty crazy, it comes in waves, but in some ways it has been quite relentless the attention the film has been getting. Just when it calms down something else happens. I’ve travelled a lot with it, and that became quite normal, to travel internationally with the film. Then the cinema release in the UK, which I didn’t think was going to be a very big deal, I thought it would hopefully play in ten or 20 screens for a week, and that would really just be publicity for the online and DVD release. But the cinema release just went crazy, and in the box office we’re up to nearly half a million quid and it’s still in some cinemas now. Just as that was beginning to become normal, we get the BIFAs and the BAFTAs, so yeah in years to come I’ll think, shit, that was a pretty special time. When I started out making the film, I thought it would be a great film, I never think of doing stuff that isn’t going to be great else I wouldn’t start it, in my head I’ve got think that it’s a good thing to do. But once I vocalised the idea and had the first few drafts done, and we almost went into production ten years ago with it, a lot of the underlying feeling in a lot of conversations I was having is that it was a very uncommercial project and quite often people would say, ‘I love the idea but I don’t think the audiences are gonna get it’. Which I think is a really problematic attitude for the industry to have, but I heard that so many times. Then the film was made, and certain people who saw it said that it’s great, and critics might like it, but there’s not gonna be an audience for it, because it’s black and white, post-sync, grainy as hell, it’s non-linear, it’s about fisherman – how can that be a commercial film? But if a film that was made for a few quid can take half a million at the UK box office alone, I think it now can be described as a commercial hit. So that’s given me a lot of faith in audiences, really, and their desire for something new. I’ve got that as an audience member, I wanna see new things not the same things over and over again, and that’s the most exciting thing, and in some ways the most surprising thing, when you’re constantly told things have got to be commercial, whatever the hell that means.

Since you started to the project to making it, something that has become a lot more prevalent in the last 20 years is gentrification. How much did that change this feature, and did you speak to many locals to get a sense for how they feel about people from London, and from different classes, coming to Cornwall?

It’s everywhere here, it’s in the air. It’s in everybody. It’s a constant issue and it’s talked about in many different forms, and it’s because it’s all linked to the economy. It’s a very complicated issue because a lot of people rely on the money that comes in from elsewhere, and while it’s great in the short-term, in the long-term it raises house prices, compromising on more traditional industries, that’s problematic. People are always talking about it, whether we know it or not, any conversation that is socially or economically specific to Cornwall, it was will be to do with gentrification. It\’s a new word for me, I hadn’t really thought of it, because all my life that’s been happening in Cornwall, but it’s more prevalent now because the gap between the haves and the have-nots is more pronounced and more discussed and it’s more black and white in some ways, which also isn’t particularly helpful. I worry when people talking about it being an issue of Londoners coming down, because I’m a Cornish person but I’m not dogmatic about who should or who shouldn’t be in Cornwall, because that’s just nonsense to get all Norman Tebbit about it, some of the most Cornish people I know in Cornwall aren’t even Cornish by birth or blood or anything, they’re people who have chosen to be here because they love the place and recognise its distinctiveness and they want to celebrate that and promote it in an inclusive way and I suppose if I have any kind of prejudice it’s not a nationalist or regionalist prejudice, my prejudice is a class prejudice. For me the problems that I try to address in the film are about entitlement and the fact that people do believe that because they’ve got the money they can buy whatever they want. Also within the film there’s the element of people believing that because they have money they can fix problems and the subsequent problems from that.

Maybe I’m just saying this because I’m British and it’s all I know, but it feels like class conflict and the complexities that derive from that, is a very British notion. So how has this film travelled, what are the reactions like around the world? Has different audiences latched on to different themes in the movie, or connected to different issues compared to how British audiences have?

Yeah it’s been pretty universal, the empathy that audiences have had for the characters, which has been great for the film, it’s a bit depressing when you go to all these different places in the world and find that the issues are exactly the same. I think class thing is, in some ways, less pronounced because we’ve still got a very conscious class system, I just listened to the news on the radio a minute ago and it’s all about our class system because there’s a whole story about the Duke of Sussex and half of the news programme was about that and we’re still obsessed with class and privilege and entitlement and all that kind of stuff. Whereas a lot of places you go to in Europe, they’re kind of beyond that, people who live in Republics, they’re further on, and in some ways they have a clearer view of what a class system is, and it’s even more pronounced for them than it is for British audiences. It’s problematic for Brits, because we have the rise of populism that is about destroying the elite and all this kind of language, but then you have this Monarchy adulation and this love of a class system, so it’s really complicated in this country. I think that’s part of the frustration a lot of people feel is because it’s so difficult to articulate the social make-up of this country.

Reading about the movie, a word I kept seeing come up was ‘Brexit’. That didn’t really come into my mind when watching the film, has that been a surprising reaction to you that people are connecting the film to Brexit?

No, not at all, because what happened in Berlin was that we sent the film over to be subtitled prior to the premiere and there’s a scene in the film where there’s a radio on in the background in the kitchen, and it’s a couple of people discussing the implications of a no-deal Brexit. I put that in there because the scene was too quiet and they needed some background sound so I put some Radio 4 on, and thought, they’d be discussing Brexit, let’s record something. We wrote something, went into the booth and did this standard Radio 4 type news piece about Brexit. Now I didn’t think anything of it because it was just a bit of background radio sound, but it happened in a scene that didn’t have a lot of dialogue so when it went to Germany to be subtitled, they subtitled the radio broadcast, so I was sat there at the world premiere and that scene came on and all the Brexit stuff was subtitled, that background had come straight to the forefront. I said to my partner, ‘fucking hell we’ve made a Brexit film’. Coming from where I come from, you have to tread carefully, because I’m from a fishing town and it’s a one-issue thing here, about the fishing policy. I thought, as the rest of the film played out, maybe nobody will have picked up on that. Anyway an hour later and the Q&A started and the first person stood up and asked me about Brexit. For five days in Berlin I was just being asked about Brexit all the time, and I sort of became the unofficial spokesperson for Brexit. I think in a lot of ways it really is about Brexit, but in a way I don’t believe Brexit happened in 2016, I think it started happening a generation ago with the disenfranchising of the working class, being completely abandoned and being put on the scrapheap, so this film has been in development for 20 years and in some ways it is about Brexit because it’s about that alienation of the working class and the feeling that working people don’t have a voice, and their frustration and that they’re being left behind or forgotten or being compromised and how that frustration has manifest itself in destructive ways. In that sense it really is about Brexit. I would never label it a Brexit film because it’s dangerous, it’s either in or out when people talk about Brexit, and what Brexit means to a place like Cornwall is incredibly complicated and people are incredibly compromised, and the way Brexit is defined these days I wouldn’t wanna align myself with any of that. Britain is Brexit in all of its different forms at the moment for me, and the film is about modern day Britain, so in that sense, I would have to concede that it is a Brexit film.

During all these Q&As at festivals, and interviews you’ve done, do you find that your own relationship with the film changes through the prism of other people’s perspectives?

Yeah, completely. People ask me who my influences are, and I’ll reel off a list of names and then I realise, I don’t know if those people actually were or if they’re just people who have been mentioned to me and I went off and looked at their work. I keep mentioning Humphrey Jennings but I don’t think I started looking at him until after we’d shot the film. But I’ve been going around saying Humphrey Jennings was a big influence, but how could he have been? What the film’s about, it has become clearer talking to audiences what it’s about. Sometimes you’ll get a real left-field idea, and I think, wow, I hadn’t thought of that. Even the title, someone said to me the other day, the title is amazing because of its double-meaning. But I just liked the word, it’s a fishing term so I stuck it in, and now the audience allow me to reverse-engineer meaning into these things that actually didn’t have much thought behind them. In Berlin I had an incident where somebody stood up in a Q&A and said that it’s great that I’d taken an ancient, traditional way of making a way and told a story of a very ancient and traditional way of life, and the form and content work beautifully together. I said, oh I hadn’t thought of that. Thank you. In the Q&A the next night someone said ‘what was your intention with the film?’ and I said, ‘well, I wanted to take an ancient and traditional way of making the film and combine it with an ancient and traditional way of life…’ Suddenly that was my stock answer. And that’s not to say that isn’t what’s happening in the film, I just wasn’t necessarily conscious of it. We’re very limited aren’t? Not just by our language but by our thoughts. Sometimes somebody just needs to give it that clarity. I did a thing for Radio 4 last Summer about the film that most inspired me and I spoke about The Garden by Derek Jarman and just by talking about it on the radio it made me realise why I like the films that I like. None of the others were like Jarman’s The Garden, but just by talking to somebody about it, I realised that’s why I like that film, or that’s why I like that film. I realised I have a very narrow taste in terms of form and theme, but that narrow taste can be disguised by the amount of different ways that the form can be used by so many different types of filmmaker. Just by talking to somebody else I had some clarity about my own thoughts.

The cast are brilliant, and Edward Rowe in particular is great. How did you find him? You talk about the classic feeling about the film, and he has that old, Hollywood face, a face it feels like we’ve seen on screen for decades.

He’s known as a stand-up comedian here in Cornwall, he’s got an alter-ego called Kernow King and he has a huge following, playing a stereotypical Cornish character who spouts his views on the state of Cornwall and the world. I knew him as that character although I’d never seen his stand-up show. But a few years ago he did some serious theatre with my partner and I met him through that. I thought he was a comic and then met him and realised there was a real seriousness to him, and when I was casting the film I thought his stature and physique, his accent and his knowledge of Cornwall and its culture, which is really studied through his stand-up, I thought he could play this fisherman. What I didn’t know is whether he could perform the stillness that I wanted in the performance, because I wanted to remove as much theatricality as I could, and he trained as a theatre actor, he’d done musical theatre, pantomime, so he relies on his physicality and gesture when he’s on stage and I wanted that to be removed from the film. So all of that subtext that he normally would communicate physically, I needed him to do that in other ways. I didn’t allow him to express himself physically, so all the subtext ends up coming out of the stillness and out of the eyes, and it’s a testament to Ed that he has all of that craft, and if he can’t express himself physically he does so in different ways, and that silent rage that he’s got is so keen to the film.

So finally what’s next? And have you already felt the benefits of Bait’s success in getting the next project off the ground? You mentioned there was a struggle with Bait to convince people of its commercial potential, has that changed now, have there been positive repercussions?

Yeah definitely. I’ve had a couple of offers for reasonably big films in the UK and a couple of offers from people to develop and produce and fund what I want to do next, and we’re actually just sorting the financing on the next film at the moment. I can say that I’ll be doing a horror film down here in Cornwall, we’re shooting in the Spring. It’s a ghost story, effectively.

Leave a Comment