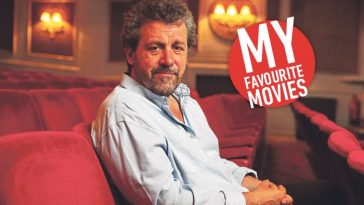

Like our interviewee Carter Burwell and his symbiotic relationship with the Coens, it’s almost impossible to not think of composer Terence Blanchard’s emotive and soulful work when recalling the films of Spike Lee. The New Orleans-born jazz trumpeter has collaborated with the director from as far back as 1990’s Mo’ Better Blues, and they have remained a tight partnership ever since, with Blanchard helping to bring to vivid life Lee’s characters and their worlds. We were fortunate to grab some time with him recently to discuss his career in movies, and how a bit of happenstance brought him into contact with Lee and introduced him to the cinematic world.

You’ve scored almost all of Spike Lee’s films. How did you initially meet?

I was hired as a session employer on some of the films of Harold Vick, who was a friend of Spike’s father Bill, who composed Spike’s early films like School Daze and She’s Gotta Have It. On Mo’ Better Blues, Spike asked me to work with Denzel [Washington] and coach him [on the trumpet]. Spike heard me playing the piano and asked me if he could use whatever it was I was playing, and that started this whole film career thing.

Given that long-standing relationship, is it now a case of Spike chatting to you about the project he has in mind before a frame of film has been shot?

Normally what he’ll do is call up and say “Hey man, I’m sending you a script, I want you to read something”. That basically means we’re getting ready to go into production [laughs] because he’ll get me involved and start thinking about things before he starts to shoot.

Did BlacKkKlansman take a little extra time to figure out at that early stage, given the almost surreal subject matter?

Not really, because Spike told me he wanted to have an R&B band for it, which was a perfect fit for the band I have now, The E-Collective. For me, the only challenge was figuring out exactly what was going to be the tone of the film. I decided on the guitar because of Jimi Hendrix. I understood what the overall political statement of the film was aiming for, and I remembered listening to Hendrix playing the US national anthem, which I thought was a very patriotic thing to do. When I heard it for the first time, it was like he was screaming, “We’re all Americans” and given the current political climate we’ve living in over here, I thought it would be appropriate to bring that element back.

Using that style also helps ground the score in the film’s 70s setting, right?

Yeah, and I wanted that distorted guitar, but I didn’t want to try and mimic Hendrix. I asked Charles [Altura, guitarist with The E-Collective] to come up with his own sound and his own take because we’re moving and pulling forward. When people see the Charlottesville montage at the end of the film, they realise that we’ve been pushing forward to current day throughout the film.

You never take the obvious route with your scores. There’s always an interesting contrast in the music to what you’re actually seeing on screen. Is that always how you tackle a project?

Well that’s all Spike, man. I have to give him his credit. Spike is the type of dude who doesn’t like underscore and action music. He likes very melodic stuff. I’ve worked with other people who have said my music is making too much of a commentary on their films, while Spike is totally the opposite. With him, he’s looking for the music to become a narrator in a sense. Sometimes the narrator will take over and give out information [for the audience]. In films like 25th Hour, Miracle In St Anna and Malcolm X, there are moments when the scores takes over everything, and BlacKkKlansman is no different. That’s Spike’s cinematic style.

That artistic choice really does separate him from a lot of other filmmakers.

Spike is just as much of a film music historian as he is anything else. He loves music. He grew up with a father who was a great musician. He respects the craft so much that he thinks of it as a character.

Music, particularly jazz, has been a huge part of your own life from a really early age. When did you discover cinema?

When Spike came into my life (laughs). I wasn’t very knowledgeable about the industry itself in terms of there being people who wrote music for movies. I just wasn’t paying attention to that – my mind was concentrated on being a jazz musician. I was on the road one day in Chicago with a day off and I went to see Star Wars. The music in there blew my mind because I’m a trumpet player and I was listening to all the brass lines and going “Man, where did they get this material from?” Then I realised that somebody has actually wrote the music for it. Oddly enough, in Chicago again, I went to see She’s Gotta Have It and while I was watching it, I was thinking how great it would be to work with a dude like that, a young guy who was committed to his craft as much as I was to mine. The next thing you know, I got a call to be on the session for Spike’s stuff and then he asked me to write some music.

Are there any other filmmakers you’d love to write a score for?

Ava DuVernay is someone I think of; I love what she’s doing. Obviously Spielberg. I like people who do those real-life stories and go in-depth with those. Even though I love comedies, the idea of scoring one scares me to death, even though I consider myself to be a funny person.

I’m getting ready to work with Kasi Lemmons right now, who I’ve been working with for a number of years. She’s also a great filmmaker. As a matter of fact, I’m in the middle of working on my second opera right now, and Kasi wrote the libretto for it.

Do you find the filmmakers you work with outside of Spike to be a different collaborative experience? Do they lean on you more?

Depends. Some of the younger folk have in the past, but I’ve worked with a number of directors – Gina Prince-Bythewood, her husband Reggie, Kasi, Ron Shelton, and they’re all very capable and have their own styles. It’s my job as a composer to help them tell their stores the best why they see fit, not the best way I see fit. The cool thing about that for me is it means you have to stretch as an artist. [Shelton’s] Dark Blue was a departure for me from what I’m used to doing, as was George Lucas’s Red Tails. I also did a film called Bunraku which was very different from anything else that I’ve ever done. Those are the kind of projects that I really love because they don’t pigeonhole me into being one thing and they help me to grow and allow me to experience new things.

- Discover here Hot Corn Soundtrack

- Music for Film: Terence Blanchard is available on CD or via streaming

Leave a Comment