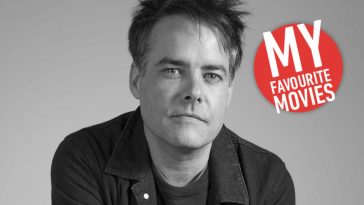

The name Dominic Lewis may not be as identifiable to cinema fans as those contemporary Hollywood composers like Michael Giacchino, James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer (with whom the 33 year-old London-born musician has previous collaborated with). But it’s only a matter of time until Lewis is recognised amongst those illustrious names, with his sterling work in Amazon Studio’s The Man in the High Castle, contributions to some of Hollywood’s biggest action adventures of late (more on these below) and his charming score for this year’s box office big-hitter Peter Rabbit steadily pushing his name up the in-demand list.

He more than ably steps into previous composer Danny Elfman’s large shoes by lending his talents to the breezy spooks and ghoul’s sequel, Goosebumps 2: Haunted Halloween, out in UK cinemas this weekend. We caught up with Lewis over the phone recently to talk about his work in Hollywood over the last decade and how the unwavering support of a fellow film composer sent him off on his career path.

You didn’t compose the first Goosebumps film. Did that make the sequel an even tougher challenge for you in a sense?

It’s very daunting following someone like Danny Elfman. I wanted to keep [my score] in the world of Goosebumps, but at the same time, put my own stamp on it. Having said that, there are moments in the score where I do use Danny’s main Goosebumps theme, which I thought was important to tie the two movies together. I just had to believe in myself a bit more than usual and get on with it, because if you start second-guessing, you end up with a bunch of crap. I just wanted to bring my orchestral sound to the movie in the same sort of ballpark as the first one, without trying to copy Danny.

You’ve jumped between many genres in your work. Was that a conscious choice?

I think it’s important to have more than one string to your bow. I like to mix it up. If you stick with one genre, your creativity can get a little stale. At the beginning of my career, I wanted to show I could be versatile, coupled with the fact that initially I’d take what I could get (laughs). It was really the combination of those two things.

Having the opportunity to work within different genres earlier on has set me up now for trying to get any film, whether it be a fantastical comedy-horror like Goosebumps or a movie about a taking rabbit. I did a lot of strange little pieces in the first few years of my career in order to be able to make the choices later on, which is really nice.

You’ve been working in the film industry for over a decade now. Can you talk a little about what was involved in being an additional composer of some pretty huge Hollywood films like Captain America: The Winter Soldier and How to Train Your Dragon. There’s kind of a misconception from some cinema fans that it’s purely the one composer who does it all.

Scoring that kind of film is a massive undertaking, and it’s very rarely just the one person [composing], especially those really big films like the Marvel movies. It’s all hands on deck really. My experience of being an additional composer ranges from when I first started with John Powell, which was more an orchestrational and arrangement role, fleshing stuff out and writing some compositions for picture. Then moving on to working with Hans [Zimmer], he’d put together his themes, and then I was left to my own devices to get on and do the cues that I’d been assigned to compose. Hans is great like that, especially in a business meeting. He will give you credit right in front of the director for the cues that you create.

I’ve also done movies with Henry [Jackman], which was a very different working experience. That involved a kind of ghostwriting, where the executive team and the directors knew I was on the crew from the production meetings I attended, but they were never really aware of how much I was involved. That process is quite common in order to get the job done. There’s no way one person can demo up 110 minutes of score for a huge action movie in two and a half months alongside director notes, picture changes and everything. It’s fairly normal for the big composer to bring in additional help.

My career as a solo composer has been mostly on work which is much smaller than guys like Zimmer and Jackman are used to. I’m in a very different place in my career then they were when I was working for them. But when you do get to that huge blockbuster level, it’s understandable that you may need extra help now and again.

You talked briefly about Hans Zimmer but Rupert Gregson-Williams was something of a mentor to you. How did he help you, not just from the point of view of the craft, but also from the perspective of working in the industry?

Rupert has been incredible. I wouldn’t be taking to you today about my career without him. He took me under his wing at the super early age of 16 when I first met him, because I was at school with his step-daughter. He encouraged me so much and would always invite me down to the studio [he was working in]. When I left school and went to the Royal Academy of Music, I was constantly in touch with Rupert, sending him my compositions and arrangements. I also helped him out on vocal stuff because I did a lot of session singing at college to earn a bit of extra cash. I did some vocals for him on his work on the reboot of The Prisoner series – little bits of pieces which kept me involved in the industry. He’d offer me programming and orchestrational tips. Anytime he was recording at somewhere like Abbey Road, I’d be invited.

Also when Rupert’s brother [The Martian and Prometheus composer] Harry was recording, he’d also asked if I wanted to go over and check it out. He put in a great word with Hans and got me out to LA and a few steps ahead of everybody else, really. Rupert basically told the crew over there that I was ready to start writing and when the opportunity came, I should be given the chance. Every time he needs a favour with his own work, I’m like “sure, of course” (laughs) because I owe him everything.

- Carter Burwell – “The Coens wanted someone who wouldn’t cost much…”

- Jeff Russo – “Legion and working with Noah Hawley…”

- Graham Reynolds – “Music is such a hard thing to talk about…”

Leave a Comment