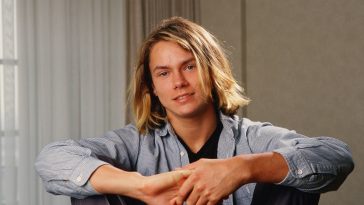

The Emmy award-winning Geoff Zanelli cut his teeth scoring additional music for renowned film composers before branching out on his own to craft some memorable scores of his own. Within the Disney stable, he penned Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales and Christopher Robin. Now, he’s returned to the world of blockbusting fantasy with Maleficent: Mistress of Evil and we sat down to speak with him about mentors, movies and music.

You have lots of composing credits to your name, both full scores and additional work. How do you still keep things fresh when you sit down to write?

Part of it is a little bit of luck. I very rarely have to do a score for the same genre twice in a row. Even if I did, I would try to find a new way to do it. Over the last 20 years from one job to the next, it’s really been something totally different. Maleficent is obviously a huge Disney family movie which required a large orchestra, and the very next score I’ve written is for a film called Black and Blue, which is a cop thriller. It’s a mostly electronic score with some guitars and my string section had eight players. It was a completely different experience to Maleficent and I think that helps in the writing to have something totally new to approach. The hardest job in my life is when I do a miniseries, where it’s more like one movie and five sequels right after. That is difficult to stay fresh – it’s more about endurance.

James Newton Howard scored the first Maleficent. Did you find it daunting following in the footsteps of one of your Hollywood peers?

Yes and no. I think the precedent for it in my career was the fifth Pirates [of the Caribbean] movie. I had worked on the first four in the series with Hans Zimmer – one of my mentors – and so that transition into doing the fourth sequel where there’s some legacy music that I wanted to use in appropriate spots prepared me for this even though I didn’t work on the first Maleficent score. That being said, it probably should have been more daunting than it was. I approach these project with a certain amount of naivety which helps me as I don’t realise how daunting it is until I get halfway through.

You’ve done a number of scores for Disney now. Do you still feel you have a level of autonomy with them, or do you have to follow a house style in a sense?

I think I have autonomy but it’s kinda in my nature to write a certain way. The movies I’ve scored which were made under the Disney umbrella like Christopher Robin and The Odd Life of Timothy Green have a tone to them which point you in a certain musical direction, anyway. It would have been a mistake to make an edgy score for Christopher Robin. It was much more wholesome and about committing to the nostalgia and sentimentality around it. I have to say, Disney are one of the few studios which really allow you freedom as to how you write the score. That’s not to say they don’t weigh in on it, but there are no obstacles. When I said I wanted a 40 piece orchestra [for Maleficent: Mistress of Evil] they said “done”. It’s a little different from the puzzle-solving on movies which don’t come with a blank cheque.

You mentioned collaborating with the great Hans Zimmer. Dominic Lewis spoke briefly with us about his experiences with him, but how was yours?

The first time I ever set foot in a studio was Han’s place in 1994. He was writing The Lion King. I was teasing him when I was over in London scoring the Maleficent sequel by saying “you’re still writing that movie?” I started out pouring coffee for him – I was a teenager then – and I grew up in that recording studio system. Then I started working for a composer called John Powell and that’s when I actually began writing music.

At a certain point, Hans started taking notice what I was doing for John and got me on board for Hannibal. It was gradual growth for me. I wasn’t an overnight success. It’s been small steps along the way, rather than a large one. When I was working on Hannibal, I was in way over my head and I was learning trial by fire. Nowadays when we work together – the last movie we did was The Lone Ranger – and in that sense, it was Hans giving me the ending of the film to work on while he did something else. We’d then circle back around when I had something to show him and finish it together. He knows what I can do and I guess it takes a little less input from him to get it to a place where it’s ready. My work on Hannibal was probably a disaster from his point of view (laughs).

The time around Hannibal must have been a really enlightening period for you.

Funnily enough, writing music back then wasn’t the hard part. I already knew how to do that. What I wasn’t aware of was writing the correct music for each scene, and that’s what you learn. You get a safety net when you’re working with a mentor like Hans or John which meant I could fail as much as I wanted within those walls and that music I was writing wouldn’t see the light of day. By the time [the score] was ready to play for the film’s director, it was as good as something that Hans and John would have written because they’d would have had so much input on it. That was a great way to learn how to write film music – from the inside, essentially.

Your CV is peppered with work on video games. Is that similar to scoring for film or does it require a different discipline completely?

Some of the work is pretty similar. In regards to the forthcoming Star Citizen – which is the biggest game I’ve been involved with – some of the work is very filmic. The ‘cut scenes’ in the game are moments that move the story forward, and they’re exactly like a film in how they’re tied into the story. The difference here being that a video game’s story takes 20 to 30 hours to tell. You have to be more careful with avoiding thematic repetition. In a movie you might write a great piece of music which gets used in various ways perhaps five or six times throughout the film. If you were to do that as frequently in a video game it would be played out fifty or sixty times, and that would be disastrous. In some ways you have to write more thematic material.

Is there a film series or genre you’re itching to compose a score for?

I love doing those fantasy movies. They’re the kind of films I grew up on. I talk a lot about the original Clash of the Titans. It was on TV all the time when I was a kid. I’d come home from school and turn cable on and they’d be films like Beastmaster and Krull and they were always on. They stuck with me and really got my imagination going. I guess if there’s a genre I’m really itching to do, it’s more of those types of films.

Leave a Comment