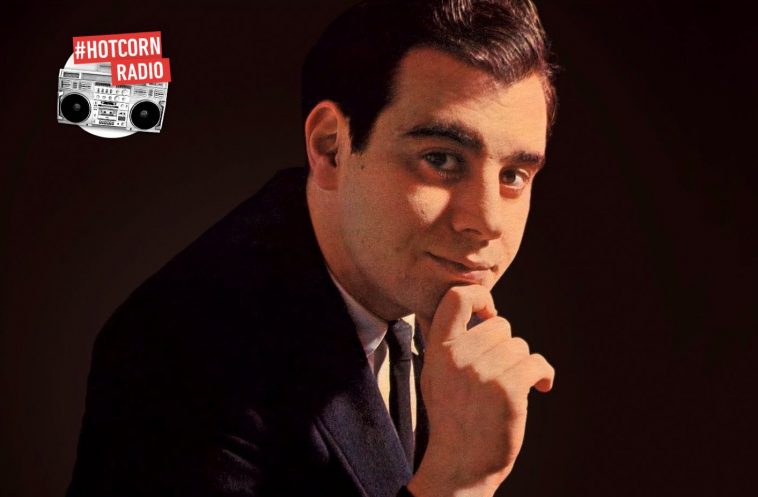

It was announced that the 86 year-old Argentinian-born composer Lalo Schifrin will be receiving an honorary Oscar at next year’s awards. Like many previous recipients – amongst them director Robert Altman and famed cinematographer Gordon Willis – Schifrin has been nominated a number of times previously yet this will be the first time he picks up that coveted statuette. Having written scores for over 100 films in a career which spans five decades, the composer is one of the most prolific in his field, and was still averaging two or three films a year in the first decade of the noughties. He even has his own Hollywood Walk of Fame, and his theme for Mission: Impossible – still such a fundamental component of that franchise – was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame a couple of years back.

With a pre-movie career steeped in jazz and breezy bossa nova, Schifrin rubbed creative shoulders with such music luminaries as Dizzy Gillespie and Quincy Jones before finding his niche as a Hollywood composer. He entered the industry just as it was heading into the glorious renaissance period of the late sixties/early seventies. Scanning his filmography from that time, it’s incredible seeing the sheer number of iconic movies Schifrin managed to score – Cool Hand Luke, Dirty Harry, Enter the Dragon, Coogan’s Bluff, Kelly’s Heroes and Bullitt.

The success of those films can be partially attributed to the composer’s magic touch and bringing his jazz-infused background to the fore of mainstream cinema of that time. Bullitt, in particular, is arguably more well-known nowadays for Schifrin’s achingly cool score than everything in the film itself, even that famous car chase.

And this is what exemplified the best Hollywood composers of yore, before the now committee-made landscape Hollywood reared its ugly head. Schifrin and Co. pushed the medium into new directions, imbuing the films they worked on with their signature musical style in the same way a renowned filmmaker might leave his or her’s auteurial imprint.

If Schifrin fell a little out of favour in the early nineties, it took, of all people, the now-disgraced director and powerhouse producer Brett Ratner to pull him back out of the wilderness, tapping the composer to score the majority of his films, including the wildly-popular Rush Hour trilogy. He even found room to give Schifrin a cameo appearance in his 2002 adaptation of Red Dragon, where his music collaborator cropped up briefly as an orchestra conductor.

The infectious joy of Schifrin’s music is very still very much evident in Rather’s films – especially the aforementioned Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker escapades – and this fitting acknowledgement of his contributions to the film industry is long overdue. Schifrin appears to have retired now – his last credited work was for one of the films in a 2015 horror compendium – so what better way to pay tribute to an artist who has left such an indelible imprint in his chosen profession?

Leave a Comment