LONDON – ‘Yes, I’m happy to do this’. We were very privileged to talk with Pat Metheny and ask him some questions about his very unique career in soundtrack’s world, from his very first score in 1979 to his favourite movie ever. «At a certain point I kind of realized that scoring was something I could do, I did fine with the films, I never got fired or anything, and everyone seemed pretty happy with the results, but I also realized that I didn’t particularly interface that well with Hollywood…». In this interview, we speak to a modern jazz genius about breathing new life into the art of film scoring from The Falcon and the Snowman (and Fandango) ’til his last soundtrack for the documentary Becoming California.

Let’s start with your first score: it was back in 1979 for a documentary: The Search For Solutions with Stacy Keach as narrator.

Yes, my first scoring gig was that science series, The Search For Solutions. Writing for film was always something I was interested in, and when that one came along it was pretty early in my thing, I had recently started my own group and was on the road almost constantly, so squeezing it into everything else that was going on at the time was challenging. I wrote the main theme right away (here’s the trailer) and from there, everything followed. (That theme became the tune The Search, which I recorded with the band on American Garage right around that time). After that, over the next few years I wrote three scores for a small but very good Boston director named Jan Egleson – Little Sister, Lemon Sky and Big Time. Each of them had some unique stories around them. Lemon Sky (here) starred Kevin Bacon and was a score where I brought in Jack DeJohnette to play solo drums – which was an idea that I later gave to my friend Alejandro Iñárritu who then used that concept for Birdman with Antonio Sánchez playing drums. Those three films were really fun because they were small and it was really just me and Jan. All of this was in parallel to the emergent technology, specifically the Synclavier, which really opened up a whole world of possibility that had just not existed before then.

And then came Fandango…

Kind of mixed into that timeline came Fandango, yes, directed by Kevin Reynolds. He really wanted me to do the whole score, but because it was his first film, they (Amblin Entertainment) kept him on a pretty short leash and wanted to bring in a more experienced day-to-day film composer. And also, again I have to emphasize that during this period I was on the road almost non-stop, so pausing everything for a few weeks or months to do a score was almost impossible. But, as you noted, The 10 minutes or so of stuff that Kevin used in Fandango became very well known, and to this day it really is quite a cult-like thing. And, I loved the way Kevin used the music, especially the dance scene at the end with “It’s For You”.

And after that?

After Fandango came a very serious offer to do the music for a film called Under Fire starring Nick Nolte. The producer of that film was Jonathan Taplin who was convinced that I should write the music. He brought me (and I invited Lyle to come with me) to L.A. for weeks to stay at a fancy hotel and work on a few scenes. The thing was that the director, Roger Spottiswoode, was a very experienced editor, this was his first movie as a director, and he really wanted Jerry Goldsmith. My reaction to that was, “Yes, you should definitely get Jerry Goldsmith!” I mean, c’mon. Together, Jonathan and Roger came up with the idea of Jerry writing a score that featured me playing guitar, which Jerry was quite into and even excited about – he said he had always wanted to write a score like that, specifically a chase scene that featured guitar, which there is plenty of in the final film. Getting to hang around with Jerry for a month or so was one of the great experiences of my life. He was amazing and it was an inspiration for me – so much so that as soon as the project wrapped, I came home and wrote music for weeks from a perspective that I never had before. Included in that bunch of music (a song from that score was used even by Tarantino in Django Unchained, ndr) is the tune First Circle. One thing Jerry said to me that really stuck with me was “You (jazz) guys always write stuff that you can already play!”…which rang true to me, so I started writing stuff that I couldn’t play….lol. So…that brings us to….

During the 80’s there was a lot of attention on me, and it was a period where folks were branching out in terms of the kinds of scores that they were using and the types of composers that they were hiring. Because I had a few scores under my belt by that time, I was getting scripts often from folks, but again, my main focus remained on my band, touring, and making records. When I heard about an inquiry from John Schlesinger however, I made room for it. To me, he was one of the directors who really understood music, the script by Steve Zallian (one of his first) was fantastic, so was the cast. I went to Mexico City where Tim Hutton and Sean Penn were filming with John, watched the shoot for a day, and went back to the hotel and wrote the main theme right there, which is what became This is Not America as well as the central theme for the film.

This was also a period where it was becoming quite a thing to have a theme be sung by a famous pop star at the end of the film. I was actually not that familiar with David Bowie when John suggested him, but I bought a few records, and the drummer in my band at the time (Paul Wertico) was a huge fan of his, and I realized he was the perfect person to sing the piece. In the end, getting to work with Bowie was another real highlight – an amazing musician. After that, lots more opportunities came along, most of which I passed on. I kind of realized that scoring was something I could do, I did fine with the films, I never got fired or anything, and everyone seemed pretty happy with the results, but I also realized that I didn’t particularly interface that well with Hollywood. Also, truthfully I was kind of spoiled by having my own band, writing my own music and kind of doing everything my own way.

What didn’t you like about film works?

The thing about film work is that kinds of human skills that are required, like being able to negociate with a commitee of eight or ten people, dealing with the assistant director’s sister’s son who is going to Berklee and thinks that part should be played by an oboe (true story!) and so forth, all of it was not something that I was particularly suited for in the way that day-to-day Hollywood composers are geared up for. Not long after The Falcon and the Snowman, I did a Gene Hackman film called Twice in a Lifetime, and I realized after that one that I would rather just spend my time doing my own thing, and kind of retired from film stuff for the most part. I don’t rule it out, but I don’t really pursue it either. Years later, one did come up that I really enjoyed which was the Italian film Passaggio per il Paradiso. It was a personal challenge for me in that I had 6 days that I could squeeze it in in between tours, and I actually did the entire thing, written and performed, in that time frame. It also featured a great performance by Julie Harris, one of her last.

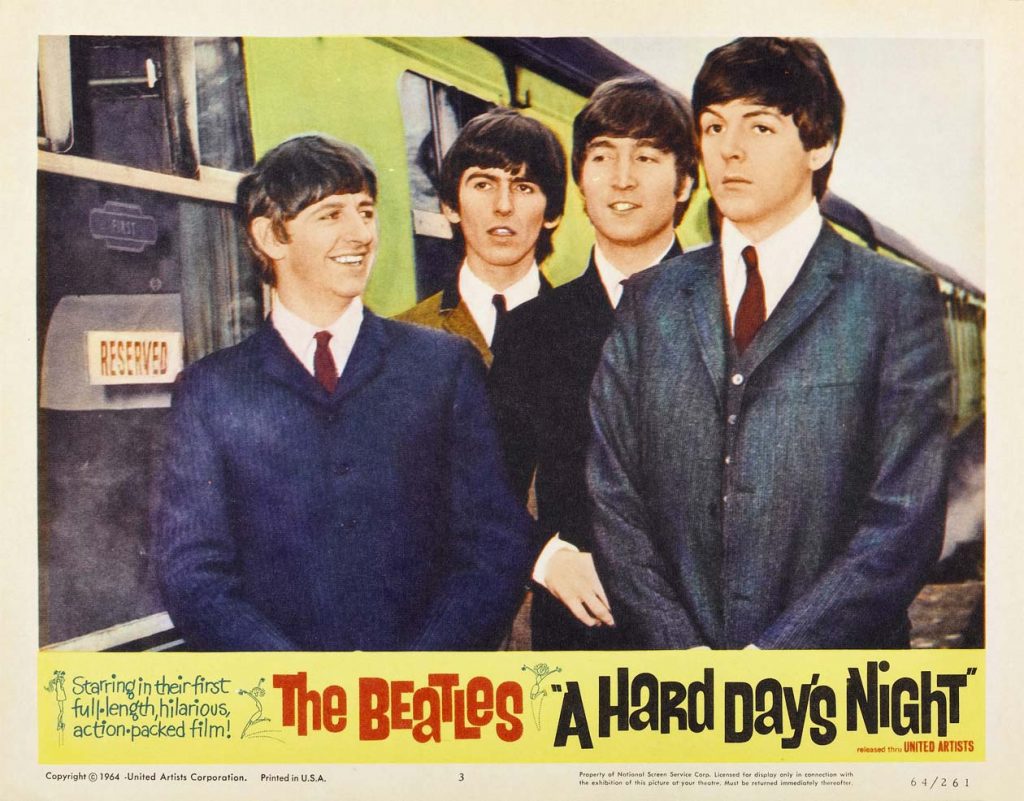

I am old enough that we could go to the Vogue theatre in Lee’s Summit, MO where I grew up, and for a quarter, watch double features every Saturday. This was the era of movies like Creature from the Black Lagoon and stuff like that. But maybe what I remember most was going to see Beatles’s A Hard Day’s Night about 10 times in a row.

Let’s speak about Becoming California OST: how did you come on board on the project?Every now and then something comes along where the folks behind it are so determined that I am the person that they had in mind for something, that if I possibly can do it for them, I try to. Sometimes folks know things I don’t know about whatever my thing might be. Becoming California falls into that category. Again, I was on the road constantly during that period, and the only way I could see being able to work on it would be to provide them with a whole lot of material and let them figure out how to use it. That is what ended up happening with that one, and it is the only one I have ever done like that.

Do you have a favourite soundtrack composer? And why?

You probably won’t be surprised that it is Ennio Morricone. To me, not just the skills that he brought to everything, but the sheer creativity and imagination that appears across his immense body of work is stunning.

You wrote the music and win a Goya for an underrated spanish gem: Vivir es fácil con los ojos cerrados. How was that project born?

That one is really unusual, and also a very special project on a bunch of levels. My best friend Charlie Haden was approached to do the music for this film but he was too sick at the time to work on it. He called me just a few days before he was supposed to have delivered the music, and he had just not been able to write anything and was kind of panicking, so he sent me a rough cut of the film over the Internet. I watched the film and thought it was an amazing picture, and that it needed a lot of music, and how did Charlie get himself into this position with a score due just a few days later? I heard in my head right away what I thought the vibe of the score could be, and quickly wrote a theme along those lines on the baritone guitar, and sent it to Charlie. Without telling me he was going to do it, Charlie sent this demo a few minutes later to David Trueba, the director.

Based on that quick demo theme, Charlie and David both called me and insisted that I had to write the score, and quickly, because it had to be done by the beginning of the next week. I had to help my friend Charlie. The thing was, I was about to leave the next day on a long-planned family vacation. There was no way I could not go. So, I ended up composing the whole score and even recording much of it in the bathroom of a cruise ship on a trip to Bermuda with my wife and kids over a 5 day period. I don’t think I have ever done anything that fast; I basically had those few days in the bathroom of that cruise ship to write the score, and because of the time constraints wound up using a lot of what was temp stuff I recorded on the ship and built around that. When I got back to New York from the cruise with the score done, I immediately flew to Los Angeles where I had rented a studio to record the score, hopefully with Charlie able to play the bass parts I had written for him. He was able to play a little, but not too much by that point.

I met David Trueba for the first time on those few days we had to record and mix the score. He had flown there from Spain. We managed to get everything done in the studio in just under 72 hours. So, from beginning to end, it was about a week in total, and I think I must have slept about 8 hours in those 8 days! But it was such a great movie it was worth it – I would have hated to have missed the opportunity and because of the schedule that was the only way I could do it. It is unusual that it has won all these awards and stuff done under those conditions. I kind of came out of retirement for that one, because it was for Charlie. Everything went way beyond the music with the two of us, but the musical connection that we had was a great reflection of our friendship as well. Also, sadly, that project was the last time I got to really hang out with Charlie, he passed not long afterwards.

What’s your favourite movie?

Cinema Paradiso. To me it’s perfect; a beautiful story, a great director, and the most perfect, amazing score of all time…

Regarding film scores in general, each situation is wildly different. And as much as it is a collaborative process with the people involved, the main collaboration is with the picture itself. The film lets you know almost instantly what it will accept and is quite brutal about letting you know what it won’t accept.There is also a part of the role of the composer to kind of fix things at that stage of the film-making process; music really can make things that might not work otherwise. Since often millions of dollars are at stake, and the composer is one of the last people with the chance to make it better, it is quite a high pressure job. I often note that folks who do scores constantly tend to look ten years older than they actually are, and I totally understand why. But the truth is, I realized pretty early on that I don’t lay awake at night dreaming about writing film scores the same way I do about improvising and playing and composing music for great musicians to play.

- JESSE NOVAK | «Scoring Bojack Horseman? An emotional process»

- CARTER BURWELL | «The Coens wanted someone who wouldn’t cost much»

- DANIEL PEMBERTON | «It’s good to jump into something very different»

- TERENCE BLANCHARD | «Spike Lee heard me playing the piano…»

Leave a Comment