Though billed as a comedy, and with a somewhat flippant take on the notion of male depression, one thing that is certainly noteworthy about Tom Edmunds Dead in a Week (Or Your Money Back), is that it’s still adding to a rather important conversation; a conversation we’re so rarely having.

Of course depression is not a gender specific disease, and yet suicide rates in the UK, for example, are three times higher for men than they are for women. Much of this is down to the fact that women often seek help, they confront their illness and are subsequently, and professionally diagnosed, whereas men are more likely to keep their problems internalised, allowing them to fester. It’s almost as though depression is seen as a weakness (it isn’t), as though at odds with the old-fashioned and somewhat toxic notion of masculinity, a dent to a man’s pride (again, it isn’t).

But the conversation is changing, and we’re starting to confront and discuss depression in men more regularly, coinciding with the fact that male suicides in the UK are now the lowest they have been in 30 years. With cinema working as a reflection of society, and a creative output for filmmakers to explore their innermost emotions, it’s imperative we continue to scrutinise over this very theme, and Edmunds has done so by placing a suicidal protagonist at the heart of his narrative.

Aneurin Barnard plays the aforementioned lead role of William, who after a ninth unsuccessful attempt on his own life, outsources the endeavour to an assassin, played by Tom Wilkinson. There can be a criticism here that the film’s playful tone and light elements are at odds with the story being told, with montages of his various suicide attempts played out as though part of a comedy sketch. While this frivolous approach could attract disapproval, it’s still refreshing to see a male character struggling with such intense sadness at the core of the film, and being so open in talking about it.

It’s something we’re starting to see more of too, as we grow as a society. That’s not to say we haven’t seen depression depicted on screen before, it’s just been far more subtle historically. Take The Apartment, it’s fair to say that Jack Lemmon’s C.C. Baxter is having a tough time of it, but in 1960 this wasn’t such an easy topic to explore, and so his mental illness is displayed more so through a physical one, as his continuing cold could be seen as a metaphor for his inability to get well. It was more overtly tackled in festive hit It’s a Wonderful Life, and though it comes equipped with your traditional, happy Hollywood ending, at the film’s core is a man questioning his place in the world, brought to life with a stunning conviction by James Stewart, of someone not appreciating the small things in life, needing, in a way, to step out of it to best understand what is truly important.

Another example is Robert Redford’s Ordinary People, which looked into how depression takes hold of a family, following the accidental death of the eldest son. But all three aforementioned examples imply there is a trigger, and that’s not always the case, sometimes there isn’t really any reason for depression, it can just take hold of somebody, with no rhyme nor reason.

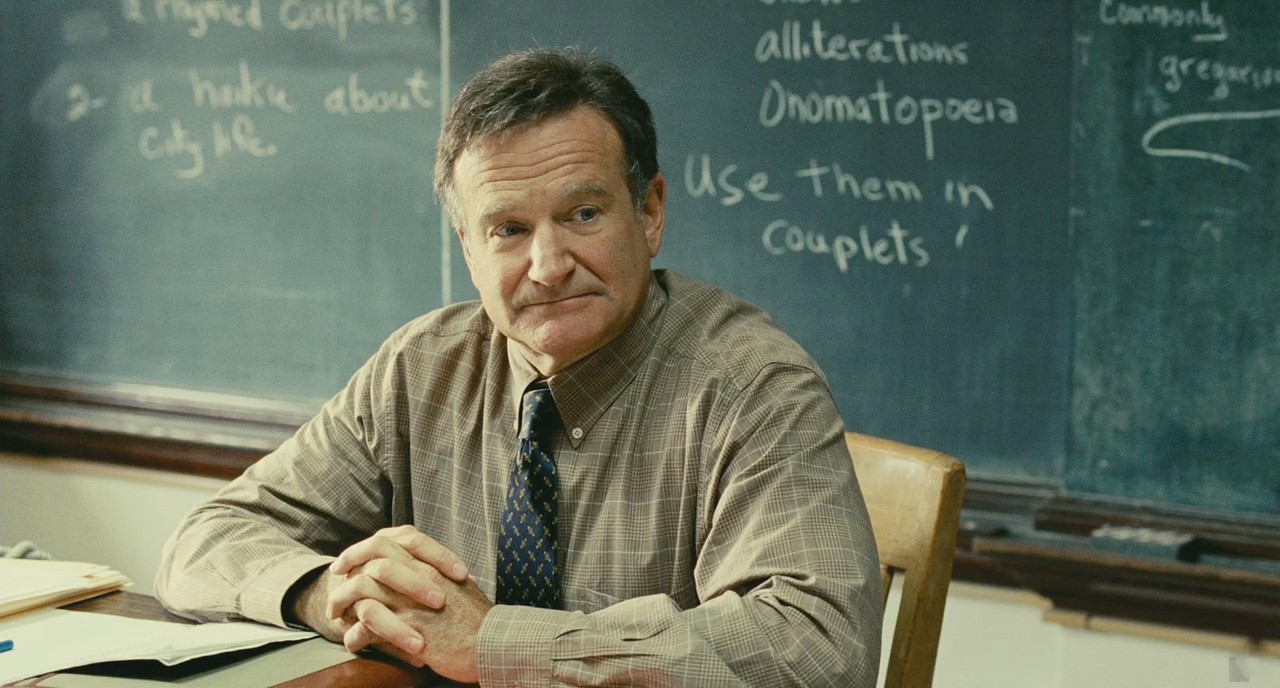

In recent years we have come to learn that the late, wonderful performers Philip Seymour Hoffman and Robin Williams both suffered deeply from depression, and within a year of each other they both starred in films that dug into the theme in quite a striking way. The former in Synecdoche, New York and the latter in World’s Greatest Dad. It’s so easy to envisage depression as being someone crying at night, screaming and shouting about their unhappiness, but it’s so, so much more subtle than that, and both performers naturally injected their own illness into the roles at hand to allow us a raw and authentic route into depression that is seldom seen on the big screen.

A Single Man is another contemporary example of a film that tapped into this very theme, bringing out a career best performance from Colin Firth, while another came in the form of The Skeleton Twins, a moving tale of estranged twins who reunite, starring Kristen Wiig and Bill Hader. Of course more recently came Manchester by the Sea, another nuanced depiction, in that Casey Affleck’s Lee Chandler is so internalised, bottling up his emotions.

This theme isn’t restricted to live action endeavours either, as Charlie Kaufman and Duke Johnson’s Anomalisa, a stop-motion animation, features no actual humans at all, and yet is about as human a tale as you could wish to see, of a man crippled by the mundanity of his existence. Another stop-motion film that succeeded in this area was the exceptional Mary and Max. Using metaphors and allowing the viewer to step out of the real world can often have such a remarkable affect, and allow us to best understand humanity. It’s what the sci-fi and fantasy genres have traditionally always triumphed in. Look at The Babadook, an archetypal horror flick, and while this instead features a woman in the leading role, it’s worth discussing in this article for it’s a striking depiction of depression, adopting the tropes of the genre at hand to tap into the protagonist’s damaged psychological state.

So yes, Dead in a Week is a little frivolous at times, but it’s exploring male depression, and one of the most vital things those who suffer with the illness must always remember is that they aren’t going through this by themselves. And art, whether it be music or film or literature, is a means of connecting the world together, to always remind us that the emotions we’re feeling, whether happy or sad, have been felt by others, it’s the most fulfilling and overwhelming aspect to the creative process that can prevent us from feeling alone.

Leave a Comment