Welcome to the Hot Corn Social Club, where our writers duke it out over their favourite films from a particular star, director, genre or theme. This week, as chosen by our fearless leader Andrea, we’re discussing the master of suspense himself: wait for it… wait for it… wait for it………… Alfred Hitchcock.

Jo-Ann Titmarsh – REBECCA (1940)

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again”. Hitchcock’s Rebecca opens just as the book does, with the narrator recounting her dream of returning home. The narrator is the unnamed drippy naïf (Joan Fontaine) who falls for handsome irascible widower, Maxim (Laurence Olivier). All the classic Hitchcock elements are here: a blonde (well, mousy) heroine, a sinister matriarch, a fantastic use of light and shadow, not to mention a variety of precipices and staircases. There are actually three matriarchal figures: Maxim’s well-meaning, bossy sister (“I can see by your hair you don’t give a hoot what you look like”), the heroine’s sneering, bullying employer, and of course the housekeeper, Mrs Danvers (Judith Anderson). Hitchcock lingers over the dead Rebecca’s sexual “unspeakable acts”, as well as Mrs Danvers’ obsessive love for her, which leads the housekeeper to perform some pretty unspeakable acts herself. Fontaine’s transition from put-upon orphan to woman fighting for her marriage is astonishing. She is well supported by a fabulous cast that includes George Sanders as Rebecca’s kissing cousin. There is romance here, but it is tinged with death and violence, which is the most Hitchcockian kind of love story and one of his best.

Andrea Morandi – NORTH BY NORTHWEST (1959)

The list is very long, from Notorious to Psycho to Vertigo, but when the moment comes to choose the title, North By Northwest stands out. Why? For many reasons but one in particular: North By Northwest is the first James Bond film, even though it came out three years before the first James Bond film (Dr. No in 1962). Think about it: a thriller weaving spies, irony and romance, moving between various cinematic locations, opening in the glass tower of the ONU and closing on Mount Rushmore. And not forgetting the Bond girl, here Eva Marie Saint. Add Cary Grant to the mix as the Don Draper-esque publicity agent (“the outraged Madison Avenue advertising executive,” as James Mason describes him) charming and clever, almost a casual presence who transforms from a minor character to the absolute protagonist. Unsurprisingly, Ian Fleming suggested Grant as Bond for Dr. No, but Connery was the final choice and history was written. Watch North By Northwest with this in mind, and you’ll understand the modern traits. A true masterpiece.

John Bleasdale – VERTIGO (1958)

Vertigo is one of my all-time Hitchcock favourites, and not simply because the boffins at the BFI used it to knock Citizen Kane off the top of its 100 best films ever list. If Cary Grant was Hitchcock’s dream alter ego, James Stewart was his nightmare one. An ordinary Joe in extraordinary circumstances, Stewart spent decades playing men on the verge of a nervous breakdown. No American star has become so iconic while being so fragile, except for Marilyn Monroe. Here, Stewart plays Scottie, a San Francisco police detective who leaves the force following a traumatic rooftop chase which leaves him with a paralysing fear of heights. Hired by an old school friend to track the man’s wife (a dazzling Kim Novak), Scottie becomes obsessed. Now justly famous for its dolly-zoom effect – a shot Spielberg would pinch for Jaws among others – the film was greeted by mixed reviews on its 1958 release and disappointing box office returns. Even Stewart, when trying to settle a dispute between Hitch and a producer, reportedly said, ‘The film isn’t that important.’ But like many films misunderstood at the time of their release, it is the initially perceived flaws – the boringness and confusing plot – that niggle to the point that you realise it’s a masterpiece. Alongside Rear Window, this is another of Hitchcock’s studies of obsessive watching and if it works it’s spell on you, you’ll be obsessively watching it for the rest of your life.

Stefan Pape – DIAL M FOR MURDER (1954)

Dial M For Murder arrived at the peak of Hitchcock’s cinematic prowess, three years after Strangers On A Train and one before Rear Window. It takes an old familiar trope – a scheme that seems easy but turns out to be anything but – and revels in it, with Hitchcock at his most mischievous, playing with his audience’s perceptions and using his sleight of hand to keep us completely beguiled throughout. It’s subtle too, filled with stolen looks and brief glances. Based on a stage play by Frederick Knott (who was also on screenwriting duties), it’s set in a single location with a focus solely on the characters that inhabit this dark world, bringing out electrifying performances from the likes of Ray Milland, Grace Kelly and Robert Cummings. But the real star here is Hitchcock, a master in full control of his tools, as a film that is emblematic of his sensibilities and brand as a director, with his cinematic imprint so blatant, even the lacklustre detectives on show would have no trouble identifying its creator.

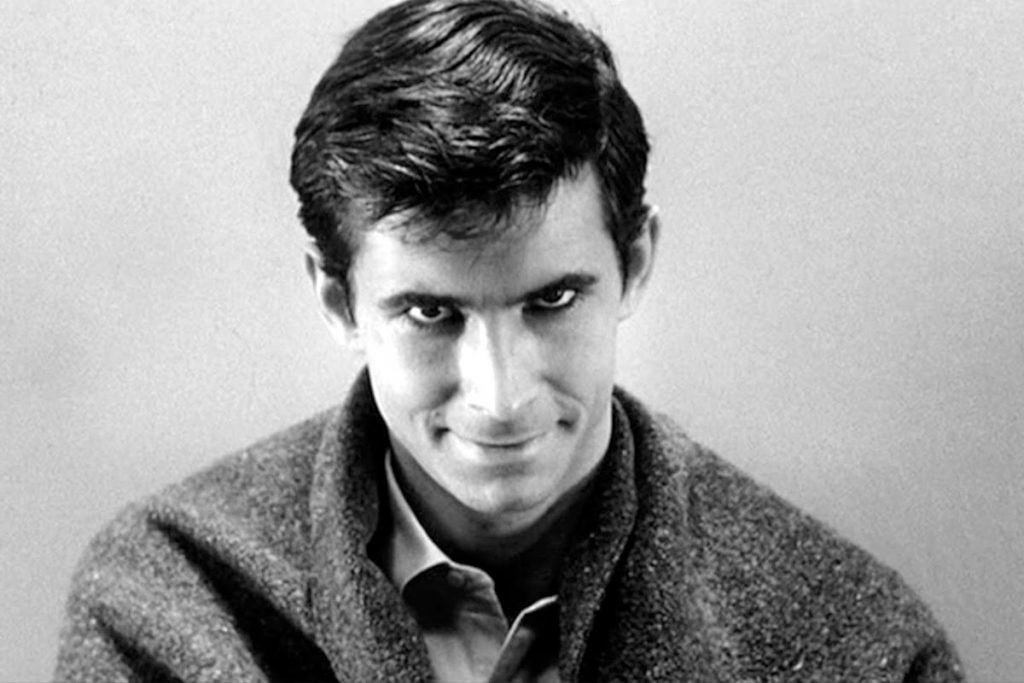

Adam Lowes – PSYCHO (1960)

Nowadays it can be easy to dismiss Psycho a little, given how its impact has been diluted over the years by a deluge of parodies, similarly-themed movies – De Palma’s reverential facsimiles notwithstanding – and Gus Van Sant’s shot-by-shot revision. The iconic shower scene has been poked, prodded and dissected numerous times – in the 90s artist Douglas Gordon even created an experimental installation focusing on the entire film (24 Hour Psycho) in which it was slowed down to two frames a second, rather than the usual 24. But strip away those myriad interpretations and what’s left – ignoring the now-dubious trans-baiting – is a landmark horror. It’s been highlighted many times before, but Hitchcock’s masterstroke is in killing off (SPOILERS) the supposed central character of Marion Crane relatively early on in the film, but only after the audience has grown attached to her. This device is largely why a contemporary offering like Game Of Thrones remains so popular. The stakes are high because the viewer is suddenly plunged into uncertainty and is left to ponder which character might be next for the chop. 60 years after its initial release, Psycho still has the power to surprise and disturb.

Greg Weatherall – THE BIRDS (1963)

Hitch had been there before with Rebecca – his first trip into novelist Daphne Du Maurier’s brooding universe. Twenty-plus years later, and with the world looking for his first move post-Psycho, he dipped into her dependable oeuvre once again and plucked out a short story with an innocuous title. The Birds satisfied the fussy filmmaker’s demands for terror and tension, mystery and intrigue. With a budget of $3.3m at his fingertips, his adaptation would utilise the best technology available at the time and, looking back, there is much to commend. Glib of tone and boasting a muted ending that frequently renders shock and deflation upon first viewing, there are still rewards for further visitations. Debutant Tippi Hedren continues to dazzle, as does Rod Taylor, and even the trailer remains a masterstroke, Alf delivering a lecture on mankind’s historical relationship with the birds, culminating in the film’s iconic squawks and Melanie Daniels (Hedren) bursting into the room declaring: “They’re coming! They’re coming!” It worked a charm then. It works a charm now. Just like the whole picture itself. There’s a reason why United States Library of Congress selected this film for preservation in 2016. Unique.

Mark Grassick – REAR WINDOW (1954)

Grace Kelly is forever remembered as the beautiful blonde who married a prince, but Rear Window proves she was so much more. The film is barely 20 minutes old when – regardless of gender or sexuality – you have to question why the hell L.B. Jeffries (Jimmy Stewart) is dragging his feet about marrying her. Forget about the “male gaze”, that first shot of a glowing Kelly appearing out of the darkness is everyone’s gaze. John Michael Hayes’s sparkling dialogue dances off her tongue like music and she glides around Jeffries’ apartment with a grace (no pun intended) that would put the dancer across the way to shame. Great Hitchcock movies aren’t rare – I was leaning towards Rebecca until Jo nabbed it first – but no character has made me fear for their safety more than lovely Lisa, and that’s integral to the film’s brilliance. Hitchcock turns Stewart’s incapacitated photographer into one of us, watching powerlessly from afar and imploring her to “get out of there” when she’s on the verge of being discovered in their suspect’s apartment. Indeed, Rear Window may seem like a sly indictment of cinemagoers, sitting in the dark, peering into other lives and passing judgement, but Hitchcock is never that straightforward. Where other filmmakers would ultimately punish Jeffries for his snooping and suspicion, Hitch prefers to unnerve by suggesting that danger and death are everywhere, so you’d better keep your eyes open.

Now it’s your turn. What’s your favourite Hitchcock film? Let us know in the comments or send an email to [email protected]

- Stay tuned for our next Social Club where we’ll be picking our favourite films by the Coen brothers

Leave a Comment