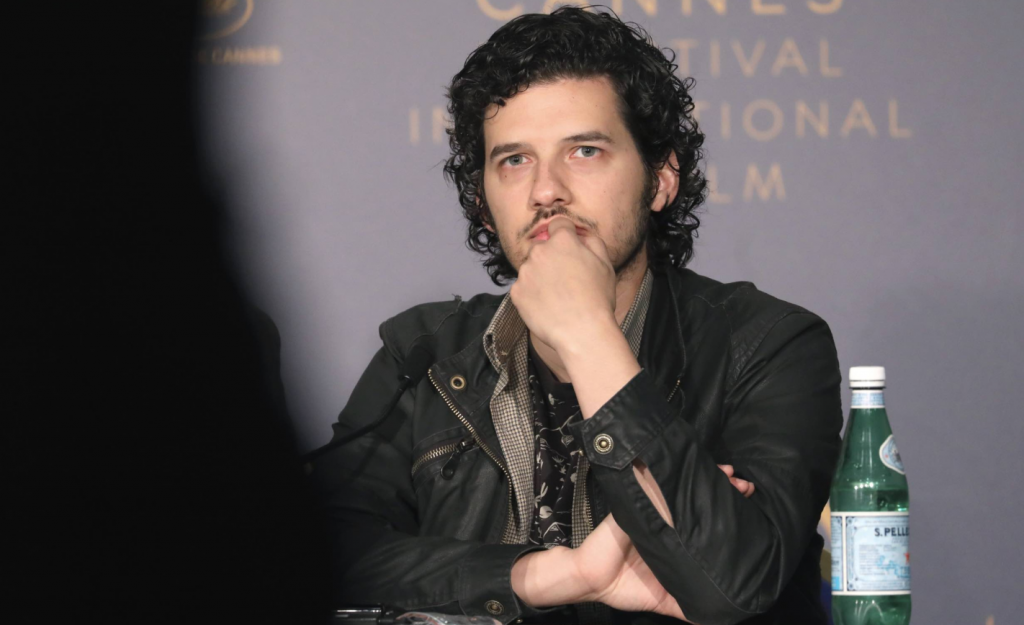

Out of the growing list of young film composers experimenting with the form, Disasterpeace (aka Rich Veerland) ranks as one of the most exciting. Coming up through the niche world of chiptune – more on that below – Veerland impressed with his unnerving score for David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows back in 2014, before crafting equally mesmeric work in the director’s follow up Under the Silver Lake. We spoke with Veerland about his formative years and bringing 8-bit nostalgia into a full-blown cinematic soundscape.

You began your career as a chiptune artist. Can you explain exactly what that is to the uninitiated?

Chiptune is usually referring to music popular in game consoles in the eighties and nineties, which was either written using a programmable sound generator, or was created by contemporary synthesisers for composers seeking to emulate those specific 8-bit sounds.

Was it that newer side to the technology which got you interested?

When I started doing music, I wasn’t doing it for games, I was doing it for fun. I started on the guitar and I then stumbled onto a community of people who were using old videogame hardware to make original music. There was also those incorporating that technology to create videogame cover versions. I was 18 or 19 at that time and struggling with the production side of making music. I found it took a long time to put together a good-sounding production of a rock track, for instance. When I discovered this alternate universe of music and I started trying to imitate those sounds, I found it was a lot faster for me to iterate on ideas.

I started to get involved in the chiptune scene. In Europe there was a thing called the demo scene, which had been around much longer [than chiptune], probably the early nineties/late eighties. That was where musicians were using Commodore 64s and DX Spectrums to make their own tech demos, essentially. They would write music and have rave parties. In the States, we didn’t really have those consoles so much, so that community who I fell in with developed more slowly than those in Europe and were more geared towards Gameboy and the [Nintendo] DS.

I worked with that community around 2006 while I was still living in New York. In North East American I did a lot of live performances for five or six years. There’s a small but passionate audience into that stuff. Doing retro game scoring never really felt like a feasible path to making a living so I developed my chops by working in music production in general, and started doing a lot of game soundtrack work. I was also doing chiptune stuff for fun and somehow I combined both worlds and that’s pretty much carried on till today.

How did you parlay that into a career for scoring for films? That must have been quite a leap?

Using an orchestra for scoring was probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but in terms of how I got from A to B, I was primarily doing independent games project, a lot of which tends to lean into the aesthetic of video game music, traditionally.

I worked on a game that came out in 2012 called Fez and it was quite successful. The director of It Follows – which was the first film I scored – was a fan of the game and soundtrack so he reached out to me. That film did really well, so it opened up other opportunities for me as far as scoring films go. Most of the projects I was being offered were more horror and it wasn’t really what I wanted to do. I didn’t do another film until David [Robert Mitchell]’s next film Under the Silver Lake, which was an orchestral score. I’ve done more scores since then, but that’s basically how I got from games to film.

Your score for Under the Silver Lake is very different from It Follows and it’s also very beautiful. Was it the director’s decision to use a more traditional means of scoring the film, or did you pitch it to him that way?

We definitely wanted to do something different and we had talked previously of stepping into the scoring process more openly, because with It Follows we had very heavy time constraints, so ultimately I had to work to a temp score. This time around we had more time and I talked about maybe me writing some music upfront and we would develop things from there.

At the end of the day, the process David has with his editor is very music-heavy, so it wasn’t practical for me to write tons and tons of music for them to try and cut to. We ended up going back to a technique that worked for us. Initially I had the idea of creating a score that would have more contemporary elements. A lot of the touchstones for David was mid-century Hollywood. When he and his editor were cutting to music from that era, it seemed to work really well for them. I think it was more in line with the vision they had, so I was up for that ride and we settled on a more noir-like vibe.

You also scored Triple Frontier recently, which feels like another departure for you, musically. How easy was it to do those broader strokes of an action film?

The biggest different was probably the creative process for the team on that film. They wanted me to write a lot of music upfront without picture that they could start to assemble a score out of and cut the film to. Due to where the film was being shot, [the team] were also remote which was an usual process for me, not being as physically close to the day-to-day decision making with the music being cut into the film. That definitely had a large role in how the music itself developed. There are themes in that movie which I wrote for a different part of the movie, or another aspect, which ended up making their way to meaning something different. In some ways the experience on Silver Lake prepared me for the orchestration aspect, but there was also enough there that kept the project fairly challenging.

Is the project you’re currently working on similar to your experiences on Triple Frontier, or is it pulling you in another new direction?

I’m doing some vocal exploration, which is something I haven’t done a lot of. I can’t seem to avoid putting myself in challenging situations.

It is a different discipline to score a video game as opposed to a movie?

For me, the disciplines have become more disparate over time. There are game composers who still operate in a somewhat traditional way. Like a film composer, they will write music and then the gaming studio will split it up and implement it. As times goes on, I think more and more folks who do music for games are getting more involved in the technical aspects – certainly how you design the music to be experienced [within the gameplay].

There’s a lot of considerations that go into a games score that wouldn’t be considered for film. In a game you have to think unilaterally about the experience the players are having. It’s non-linear, generally. There also opportunities [in gaming] to do thing which are much more unpredictable. You can mimic some of the most avant-garde compositional techniques because of the software. For someone like me who is into that stuff and appreciates the creative possibility spaces, I find it realty compelling. It’s something you generally wouldn’t do on a film score because it’s impractical to do.

Do you think the scope you’ve had in the gaming world has helped inform your movie compositions?

The approach to writing from inspiration without any visual synchronisation for a film can be very similar to a game. When I’m writing for a game, I might not be viewing any footage. It could be concept art or screenshots. But the general technique I use for scoring films is ‘to picture’, so both can be a different beast.

Do you see your future straddling both worlds, or are you completely locked in to cinema?

Right now I’m working in three different mediums, so I’m all over the place, really. I just finished a game for Apple Arcade and I’m on another game project which is pretty long term. I’m working on another film and also an immersive theatre project. I don’t really discriminate as far as what kind of medium I’m in. It’s more about the individual project and whether it’s a good fit for me.

SOUNDTRACKING | THE HOT CORN SERIES

Leave a Comment