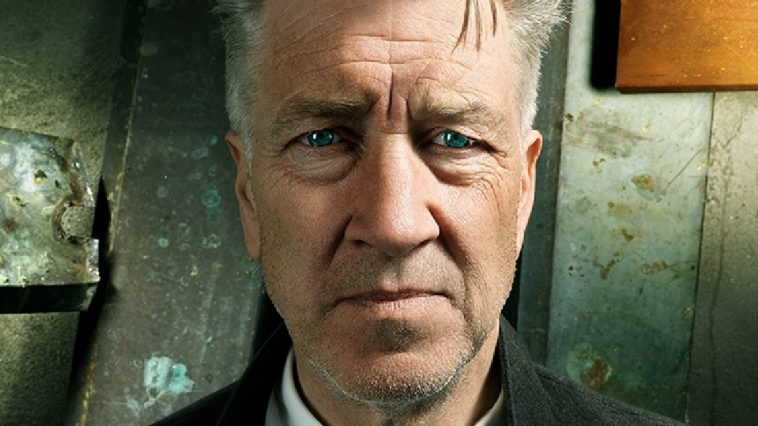

Although hardly prolific – just ten feature films in a little over 40 years – David Lynch’s filmography comprises the kind of unique cinematic landscape that leaves fans in awe and coming back for more. His name became an adjective – Lynchian – describing the dreamlike, often disturbing, perplexing and darkly comic style permeating his work. He’s also inspired countless filmmakers, from Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko to Panos Cosmatos’ Mandy.

But the Montana-born filmmaker almost came undone trying to fully realise his surreal nightmarish debut Eraserhead. Said to have been inspired by his fear of fatherhood following the birth of his daughter, the film was a five year slog to the screen, eventually leading to the break-up of his first marriage and clashes with his own family who were mystified by why he would channel his creativity and obsession into what they could see was only a bizarre waste of time. But Lynch’s perseverance paid off handsomely. The film was embraced by an audience hungry for the esoteric and Eraserhead almost immediately became a prominent fixture on the ‘midnight movie’ screening circuit, both mystifying and captivating those who saw it.

One of those cinema-goers was, of all people, Mel Brooks who fell in love with the film and tapped Lynch to direct The Elephant Man, the biopic he was producing of severely deformed Victorian-era cause célèbre John Merrick. A shrewd move by Brooks, the film proved a hit with audiences and critics, allowing Lynch carte blanche with his next project, a film which almost became his undoing as a filmmaker. After being briefly courted by George Lucas as a possible director for Return of the Jedi, Lynch decided instead to take on a hugely ambitious adaptation of Frank Herbert’s seminal sci-fi novel Dune. The results saw his career flounder when the costly film failed to find a big audience and led to Lynch denouncing the project after what he saw was an infringement on his creative vision by the producers, who had final cut.

Despite his grievances with Dune producer Raffaella De Laurentiis, it was actually her infamous father Dino who offered Lynch a career lifeline by funding his next feature and giving the director complete freedom in his artistic choices. The resulting film, 1986’s Blue Velvet, not only saw Lynch come back in a big bad way, but the film’s success allowed him to forge his own path once more. In fact, all of his subsequent films have continued in taking a recognisable genre staple and imbuing it with otherworldly atmosphere, be it a road movie infused with a Wizard of Oz subtext (Wild at Heart) or the disturbing portrayal of identity disorder masquerading as neo-noir (Lost Highway). Even his seemingly more conventional (for the first series, at least) TV soap opera-like world of Twin Peaks was brimming just under the surface with undiluted weirdness.

Another initial TV venture, Mulholland Drive, was reconfigured for the big screen and has subsequently gone on to become, arguably, Lynch’s most celebrated work. For this 2001 fable the director turned his gaze towards the dark underbelly of Hollywood and the resulting film regularly sits high up in those best-of century lists compiled every few years by respected cinema publications and venerable film critics. But another remarkable film in Lynch’s resume which sometimes gets a little overlooked due to it being a more conventional, even family-friendly affair, is 1999’s hugely moving and life-affirming The Straight Story. There’s still an unmissable Lynchian quality to the film, stemming largely from the story itself of an elderly World War II veteran (played with utter perfection by Richard Farnsworth) who drives his 30 year-old John Deere lawn tractor across two states to visit his ailing, estranged brother Lyle (Harry Dean Stanton).

Leave a Comment