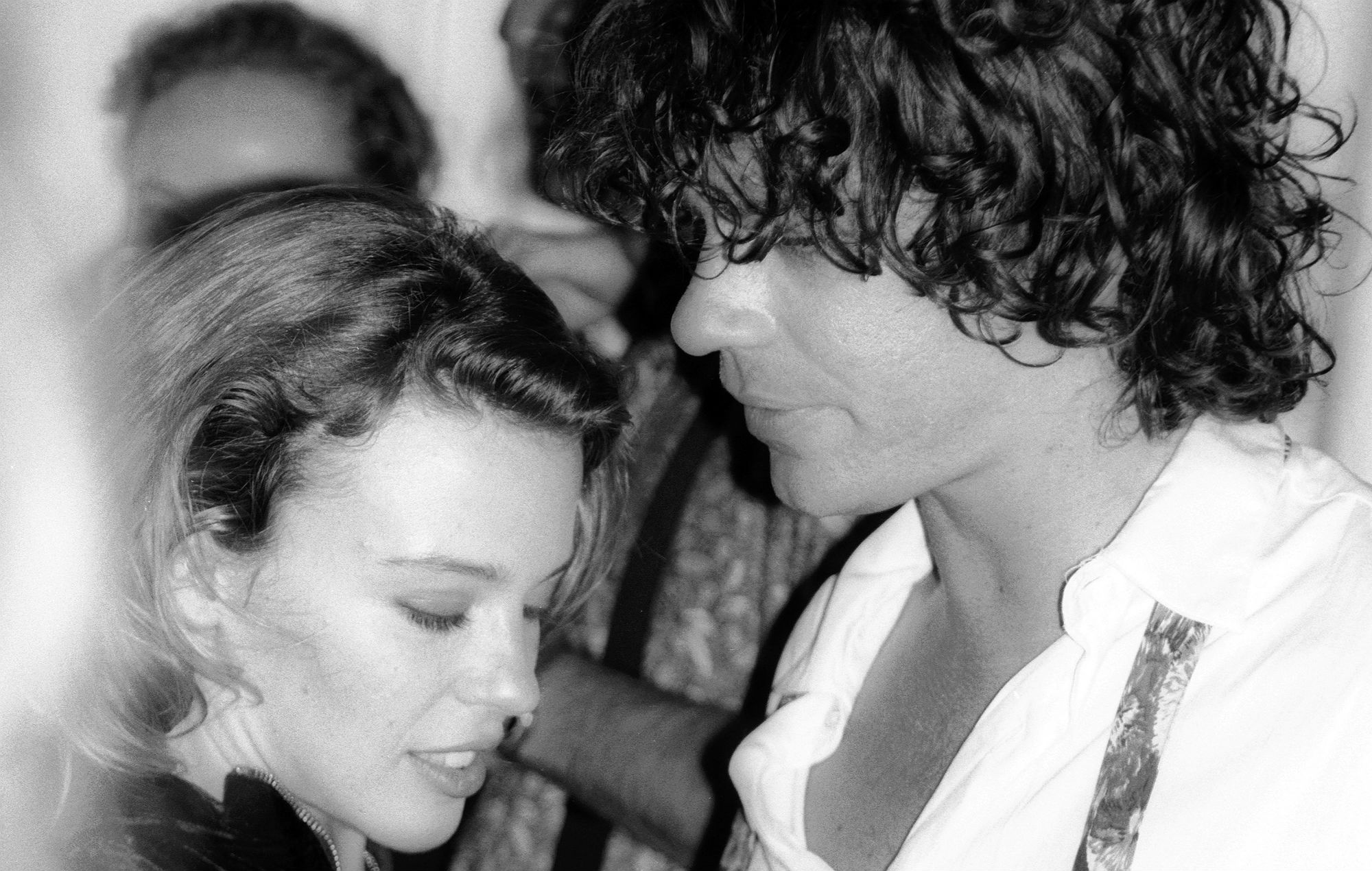

You could argue that when it comes to documentary filmmaking, the role of the director is to be impartial. But such is the love and respect and gratitude towards Michael Hutchence in the feature film Mystify, we’ve decided to let this one pass, for Richard Lowenstein was a close friend of the subject, and this enriches the material to make for a moving and compelling watch. During the London Film Festival, we sat down with the Aussie director to discuss this project, and what Michael Hutchence meant to him.

So how did you guys first meet?

We met on the set of the first music video they got us to do, which was in 1984, I think, Burn For You. I was up in North Queensland in a ratty motel and they were playing at an outdoor venue, and in those days it was all travelling around by bus and staying in motels, so they were all lounging around by a motel pool. Me and my film crew at the time were Melbourne punks, graduates from film school, wondering who the hell were all these sunbathing types, because we didn’t really like the sun, we were children of Nick Cave. Within a few hours we were just struck by them, their friendliness, their humility and their normality, they didn’t have that posey rockstar thing, because I had worked with a few rock stars at that stage. Through the making of that video, we ended up in London and the South of France. I initially said I couldn’t do it because I said I had a film at the Cannes Film Festival, but they told me to do the first half in Queensland and the second half in London, and because I was going to Cannes they didn’t need to pay for my ticket. So we ended up finishing in London and then it was all set in stone and we were all friends, and more videos came, and it just kept going, right through to the very end.

Documentaries, in the same way a fictional drama, they require charismatic lead roles and characters, and in this instance that’s a given.

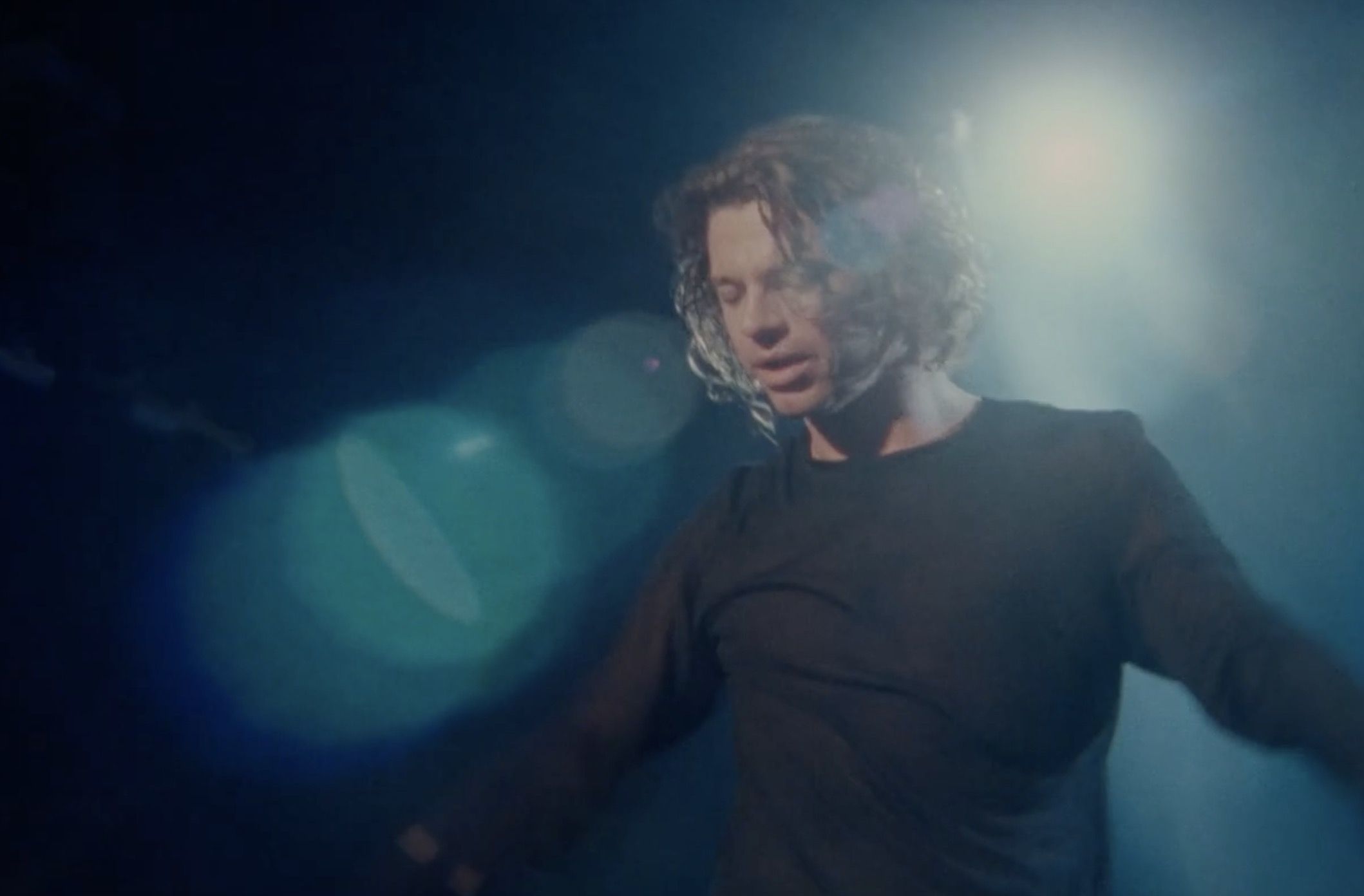

I don’t think I would’ve made it without who he was and his charisma. I remember when we would do the videos and invariably there’s the key vocal shot, and you’d do one take and he’d be warming up and then you’d do another, and usually on the third take something would happen, he would relax enough and something that would happen that would just be magic, you’d watch this one take go for five minutes. We all knew he was good on stage, but then there’s this charisma and this connection, and you’d go ‘I think we got it’. You only see that in some of the very experienced actors, whether they be stars in Hollywood or actors that really know how to light up a screen, the Jack Nicholsons and Robert De Niros, and it’s not do with attractiveness, because yes Michael was handsome, but he’s also not in another way, he had his acne scars that he was terribly insecure about. He hated the look of himself usually in the videos, he’d complain to me why I lit him a certain way. But the charisma was in the eyes, when he talked to you, and not just me, but a waiter or anyone, he’d really connect, and nobody else existed in the room. It wasn’t some mad Rasputin thing, he was listening and he was interested, which is such a rare thing. Normally in conversations people are thinking about what they’re gonna eat when they get home, but he was totally focused on what people were saying, like a sponge.

Having an emotional connection to the subject could be detrimental to a film because it can remove a sense of impartiality, but in this instance it felt like a film enriched by the love that came from you. Do you think the friend and the filmmaker blended quite well?

I can’t claim all the love, but yeah I interviewed everyone who knew, only very few escaped through my net. The love everyone has, even the spurned girlfriends, the resentment goes and it’s like everyone has this love for him, because he was, underneath all the trouble he might’ve caused, the cheating or whatever it was, there was this knowledge that he was a really good person, he was just trying his best. That was my agenda as well. It’s why we started the film with the quote ‘what is your worst feat?’ and he says, ‘not being loved’ – and that was the theme of the film. But I do agree and it’s why it took me 20 years to decide to do it because I thought I was too close to the subject to give an objective portrayal. But then 20 years went by and nobody else had done anything that I even recognised about who he was, or put what I believed was important about him down on screen, or audio or anything. There was so much material there I just felt to be authentic it had to reflect the love, not only from me but everyone felt. It was interesting because as a group of filmmakers making a film, we kept on having to pull back and try and objective, to make sure it wasn’t a love-fest or whatever, so we had to pull back and show the warts and all.

Which is where being so close helps too, you know the flaws.

Absolutely. I’m not there saying ‘oh he was wonderful’. There were times, especially at the end, he was a complete and utter dick. Those who loved him best would try and tell him that. Like that fight with Bob Geldof, we tried to tell him that he had to understand that Bob was their father, of course he wants to be their father and not just sign them over to you. So you’d fight with him and have differences of opinion, and we needed to have that in the movie.

We’re so consumed by technology, and like you said before, when speaking to Michael he gave 100% of his attention, which feels like a rarity. Do you think he represents a type of person we don’t come across anymore?

That’s a very apt point, Michael represented something that was so against everyone’s current, including my own, obsession with tablets, it’s like an episode of Black Mirror out there, everyone is out staring at their phones and he was basically into these large all-encompassing sensual experiences, so actually I think would’ve embraced new technology. But the sensuality was very real, it wasn’t technology, it’s raw, it’s a connection, you cannot define that look down a camera. I did make it as a cinema experience and one of the reasons I took all the talking heads out, I wanted it to be immersive and dramatically involving, and really sweep you away with his sensuality, and the performance and the magnetism that he gave out.

Was this experience quite cathartic? Did it close a chapter for you in some ways?

Well I certainly feel I owed him. He changed my life, he was the lead actor in a feature film that I made and he made it happen, it wouldn’t have been funded otherwise. He handed me so many extreme and memorable experiences, filming in Prague and everything. I felt that I owed him an honourable portrait. An honourable piece for the record books. So yeah it was cathartic, but I must say it has had the opposite effect, I had been a bit released from him and this story and I’d stopped dreaming about him, but getting back involved in it again, suddenly the dreams came back, and I know all the band members still have them where they think he’s still alive. All that sort of stuff. So it did bring that up. I’ve done a lot of therapy in my time but I haven’t brought up Michael in any of my sessions so it kind of is a way, an acknowledgment, a thank you, an apology for not knowing what I know now and not jumping in there when he did have these mental issues, and trying to grab him and sit him down, help him do something about it, stop being a nomad, even for six months and start dealing with what you’ve got. But who could do that with Michael? He was always on a plane to the next station, and that was his life. But he grew up like that, he grew up in Hong Kong living in a Hilton hotel when he was young. His family loved celebrities and they were surrounded by models, but luckily he had the skills because he was sort of destined for that nomadic lifestyle. I think had he not been a pop star he’d be wandering off into the desert or something.

Leave a Comment