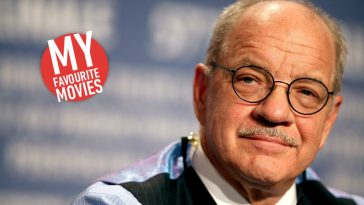

LONDON – The name might not be one that rings a deafening klaxon bell of recognition for many in English-speaking territories but, thanks to the BFI, there is an aim to right what many of his compatriots no doubt view as an egregious wrong. With a comprehensive retrospective currently underway, the floor now belongs to Marco Bellocchio, the spotlight shining upon a distinguished career of over 50 years marked not only by esotericism and an intellectual rigour, but packed with political over/undertones too. His career launched in the swinging 60s with the stirring Fists in the Pocket – a film funded by his family and shot on their property – and since then he has traversed a gamut of styles, documenting Italy’s changing attitudes along the way. His most recent feature was the Berenice Bejo-starring Sweet Dreams in 2016 but, with the upcoming Il Traditore in pre-production, this 78-year old from Bobbio in Northern Italy is showing no signs of slowing down.

Raised through a strict Catholic upbringing, his early indoctrination into the strictures of organised religion failed to fuel any lifelong devotion. In fact, much of his output has been critical of the Catholic faith and none more so than his critically acclaimed Palme d’Or nominated My Mother’s Smile (2002). A staunch libertarian, his political engagements have not been confined to celluloid either. Not only is he a former member of the Communist Union, but he also ran as a candidate for Italian parliament in 2006. Revered in his homeland and overdue wider appreciation overseas, this contemporary (and friend) of Pasolini and Bertolucci sat down with the our very own Greg Wetherall to talk about his views on faith, personal picks from his oeuvre and the state of politics today.

Did you go back to your old films in preparation for this comprehensive retrospective at the BFI?

No, I didn’t watch any of my past movies, but with something as important and comprehensive of my career, such as the BFI retrospective, it is a pleasure to be physically present for the beginning of it. Even though I am still active and working, the pleasure (derived) from the appreciation of the work done by the BFI made me happy to be here.

Your career spans over 50 years. As time goes by, is it harder to find inspiration? And do you still wish to reflect contemporary culture?

In my youth, I had to confront contemporary issues more than the overall picture of finding recurring themes in every story that I tackled. But there is always a link with the present now in whatever I do. With the accumulation of experience, you start to see contemporary themes, even if you do something by Chekhov, for example.

Faith, family and a sense of obligation are recurring themes in your work. Is there a hint of autobiography at play here? Are you, for example, reconciled with your own atheism?

I don’t call myself an atheist, because that would be a political stance. I call myself a ‘non-believer’ because I do not believe in life after death, but there are certain Catholic priests that I know that would assert that I am a believer. Then we have to discuss the semantics of what the word means. I define myself as a ‘non-believer’ insomuch that I believe that life is what is around me: this worldly life. Even in Catholic churches, the whole concept of the afterlife has changed a lot. When I went to school, the vision was still harking back to Dante. You had the circles of hell. Certain types of sinners would have a certain type of punishment. Nobody believes in that any longer. What constitutes the overall catholic belief at the moment is a life after death, so there is ‘a something’. What that articulates as has diverged from the theatrical representation of the afterlife. Just to delve a bit deeper, I have a friend who is a Jesuit, who has detected signs of my meandering belief in My Mother’s Smile, because there is a character who curses and blasphemes. Implicitly, by having someone who blasphemes, (you have to concede) ‘who are they blasphemous against?’ There is an implicit acknowledgment, if you like, of some sort of divinity in that.

You’ve dealt with politics with both a big ‘P’ and a small ‘p’; both in your films and you’re your personal political engagements. How do you feel about Italy’s current leaning towards the right?

Politics, as it existed once upon a time, were linked with ideologies and political parties. It doesn’t exist any longer. If you think about it, the way we define politics now with a capital ‘P’ is economy. Previously, economy was considered, yes, but it was always a by-product. Nowadays, politics with a small ‘p’ is how we relate to each other, how we lead our lives. The world has changed completely. Now, when you talk about a great big issue, you highlight how it acts within the economy. Say you reduce unemployment or something about the national debt: it’s not acceptance of the word (by its own) definition any longer (but how it is within the context of the economy).

If you had to steer the uninitiated towards three films from your own canon as an introduction to your work, which would they be?

Bearing in mind that everyone is free to choose, I would say Fists In The Pocket, Devil In The Body and Vincere, because I felt very much alive – not that I didn’t with the others – but with those, the challenges that I faced brought forward that feeling, as there were internal and external fights to realise them. With those three in particular, there was a true adversity to overcome.

The Marco Bellocchio retrospective runs throughout July at the BFI.

Leave a Comment