It is hard to overstate the importance of Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita to world cinema, but let’s try anyway. Released in 1960 when Stuart Sutcliffe was still in The Beatles, Fellini’s movie follows gossip journalist and failed novelist Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni) as he wanders Rome looking for stories, chasing women and an ideal of happiness that always seems tantalisingly close and yet agonizingly far. On the surface, it’s a sweet life of cool detachment and careless hedonism, but there’s also a dark side as his girlfriend is driven to attempt suicide by his constant philandering and a gnawing sense for Marcello that his life has no meaning.

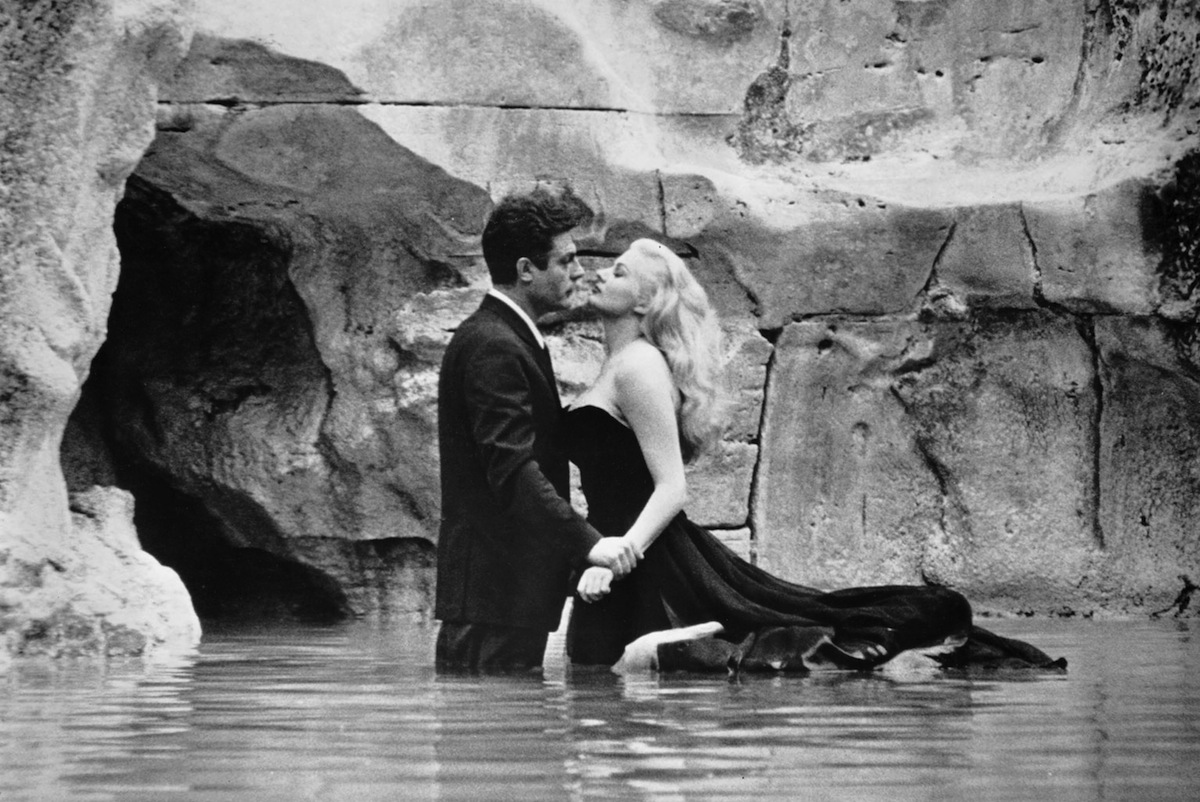

For an Italy still recovering from the bombing and humiliation of the war and haunted by the compromises and guilt of fascism, La Dolce Vita was the first international blockbuster. It promoted an idea of Italian melancholy cool. The mopeds and the suits, the sunglasses and the drinks, Rome itself looked gorgeous – the Trevi Fountains – and Marcello Mastroianni was an instant superstar. Ironically, in the films the Italians are all obsequiously adoring of American glamour in the form of Anita Ekberg’s busty screen goddess and her drunkard actor boyfriend, but it is the Italians who have the true style rather than the brutishly dumb yanks. It isn’t a huge surprise that the film inspired an entire subculture with the Mods using it as a fashion bible.

And yet Fellini’s film is not only about surfaces but also what lies beneath them. The glitz and the glamour are fun and the film constantly stays up all night. Frequently the dawn coming as the characters finally take their way home. But Fellini was as full of contradictions as the young / ancient country that produced him. Working first as a caricaturist, he got into films as a writer, providing scripts for the neorealist godfather Roberto Rossellini and Fellini’s first directorial efforts, such as I Vitelloni and La Strada – were in a similarly neorealist vein. But Fellini was too in love with the fantastic, the operatic, the carnival and the circus. The sacred and profane come together in the very first shot of La Dolce Vita as a statue of Christ is helicoptered over Rome to the Vatican, its shadow passing over the new housing being built and the girls sunbathing on the roofs.

For Marcello, his search for love is confounded by his fickle urges, while his need for some deeper meaning is frustrated by the meaninglessness of his day to day work. This contrasts with his friend Steiner (Alain Cuny), a serious intellectual and family man who relaxes by playing the organ in an empty church. Through a series of episodes we watch as Marcello gradually loses his dignity and his integrity. Although the film would be condemned by the church and banned because of its frank portrayal of sexual promiscuity, it is – while never a judgemental film – a deeply moral one.

Andrei Tarkovsky, Ingmar Bergman and Martin Scorsese would all sing the film’s praises. Woody Allen would remake it as Celebrity, as he also remade 8 1/2 as Stardust Memories. The word Paparazzo would enter the language via a character from the film, a photographer friend of Marcello’s who even snaps a shot of Marcello getting punched by a jealous boyfriend. But more than this, we are still living in the world of easy fame and instant gratification, searching for love and meaning in the midst of the noise and the laughter even as the morning light begins to break the night for good.

- Federico Fellini at 100 | Life of a Cinematic Genius

Watch La Dolce Vita now on CHILI.

Leave a Comment