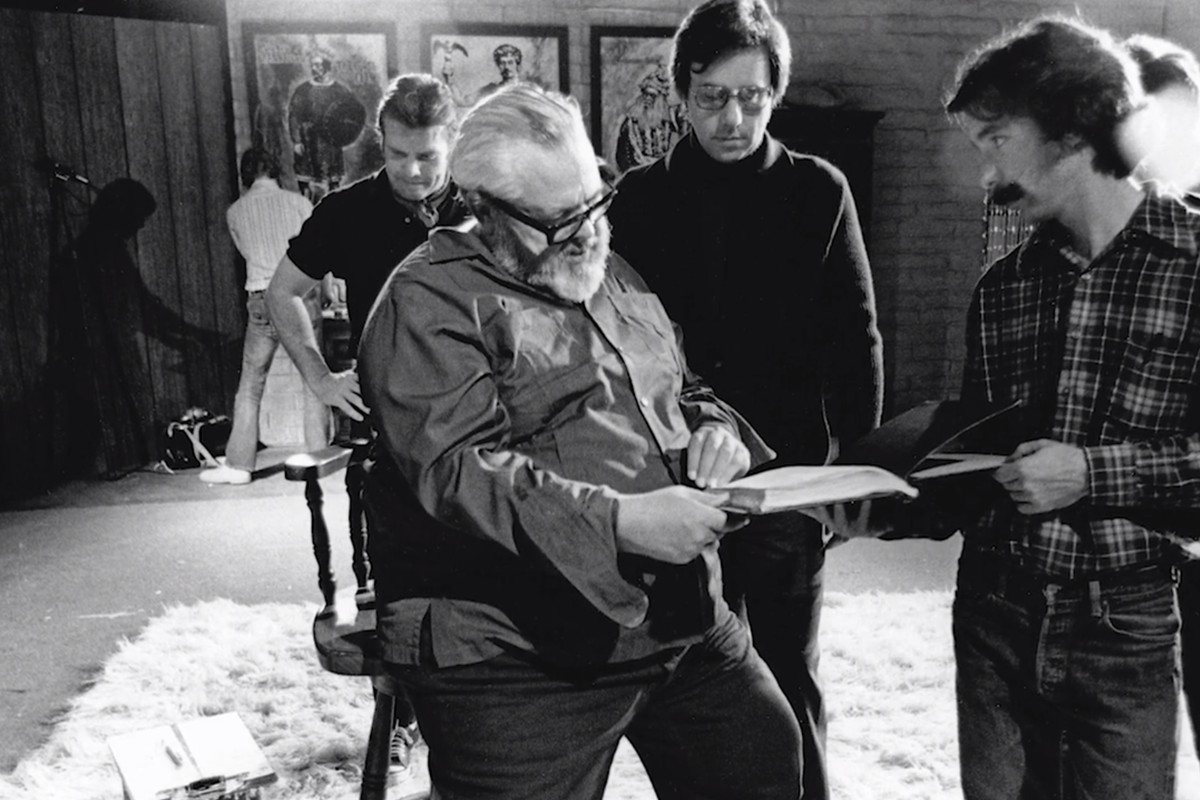

It’s hard to imagine, but there was a new Orson Welles film in 2018. Despite having been over 30 years since his death, finally The Other Side of the Wind has been completed, and is available to watch now on Netflix. But that’s not all – fans of the raconteur auteur can be treated to a documentary on the making of this troublesome film, in Morgan Neville’s They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead – and we sat down with the Oscar winning filmmaker to discuss this fascinating piece of cinema. Neville explains to us the impact Welles has had on him as a movie fan and creator, and why he feels there has been a resurgence of late into the great man’s work.

There seems to be an Orson Welles resurgence at the moment, why do you think that’s happening now?

It’s funny because I talk to a lot of people under 30 who don’t know who Orson Welles is, which I find incomprehensible, for such a towering figure in my life. I think, you know, he was such a heroic figure, kind of a father for independent film in many ways. The work he was doing in the 70s, he was the most guerilla filmmaker there was. He didn’t care about what was popular, he cared about what he thought was great art, and he felt had an important message. As an artist, that’s exactly what you want to be inspired by, somebody who cared not what the culture valued, but what they thought was important.

Is that something you almost have to teach yourself? Or did that come quite naturally to you?

No it’s hard. It’s hard because filmmaking is a popular medium and an expensive medium, and Orson dealt with that all the time, so it’s hard to balance the business of film with the art of film. I think it has become a lot easier because of technology and everything else, you know, we’re not shooting on 35mm film, so the cost of production has made it that much freer. I think Orson would have loved to be a filmmaker today. I feel like that Orson was a character who I got so much inspiration from, even making the films. Part of the reason I became a documentary filmmaker was F for Fake, his documentary he made in the 70s, which is brilliant and so experimental. It’s fantastic. So my film was kind of a homage to F for Fake.

He speaks frequently in the film about the beauty of accidents in filmmaking…

He said “the director’s job is to preside over accidents”.

What would you say across your career has been your best accident? Though I guess in documentary filmmaking it is, by its very nature, spontaneous.

It is, I think it’s the opposite. When Orson talks about that, seeding chaos into the scripted world, I feel like in the scripted world you’re trying to imbue the tired tropes of scripted storytelling with the vitality of real life and the chaos real life, and the surprises of real life. In documentaries, you’re trying to impose some sense of narrative order in the chaos of real life. So I feel like what I’m trying to do is to look at the randomness of a person’s life or of a story and try and figure out how it makes sense as a story, so it’s kind of the opposite impulse in a way. I feel like when I look at a subject it always stars at pure chaos and then I’m trying to look for shapes and try and figure out how to tell a story out of it.

The Other Side of the Wind looked like a wild, unique set. If you could go back and be on any movie set in the history of cinema, what’s the one you’d most like to have just spent a day on?

I mean that would’ve been an incredible one. Being on set of this would’ve amazing. But honestly I would’ve loved to have been on set of a Peter Sellars film and watched him work for a day.

So finally, have you started on your next project yet?

I haven’t.

That must be quite exciting because there’s a million stories out there, which one is it gonna be?

I know, but it’s knowing how much of your life it’s going to take up, that you have to choose wisely.

Leave a Comment