Celebrated British director Steve McQueen is back with an anthology of five films – Small Axe – charting the black West Indian experience in London in the 70s. McQueen has made important films about sensitive topics in the past. His debut Hunger, starring Michael Fassbender, was an impressionistic retelling of the death of IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands. Shame charted a frank account of sex addiction also starring Fassbender. With 12 Years a Slave, McQueen became the first black director to win an Oscar for Best Picture and added a high profile testament to what for Hollywood was a mostly untouched chapter in American history. Widows was altogether less ambitious: a crime thriller which nevertheless proved his flexibility in working in genre as well as boasting a powerful set of performances from its female leads.

And yet it is arguably the Small Axe anthology which will firmly place McQueen at the top of the list of British directors currently active. This is partly because for the first time McQueen is working on his home turf, tapping into the experiences of his family and himself growing up as well as his community and its history. Of the five films, we’ve had the opportunity to see three: Mangrove, Red, White and Blue and Lovers Rock, but I’ll confine myself to two for this article. Mangrove tells the story of a Caribbean restaurant in Notting Hill owned by Frank Crichlow (Shaun Parkes). The restaurant becomes a base for the community of locals, activists and thinkers. However, it also attracts the attention of a racist policeman who targets the restaurant again and again for particularly destructive and unwarranted raids. During a demonstration, nine men and women are arrested for riot including the leader of the British Black Panther Movement Altheia Jones-LeCointe (Letitia Wright), and activist Darcus Howe (Malachi Kirby).

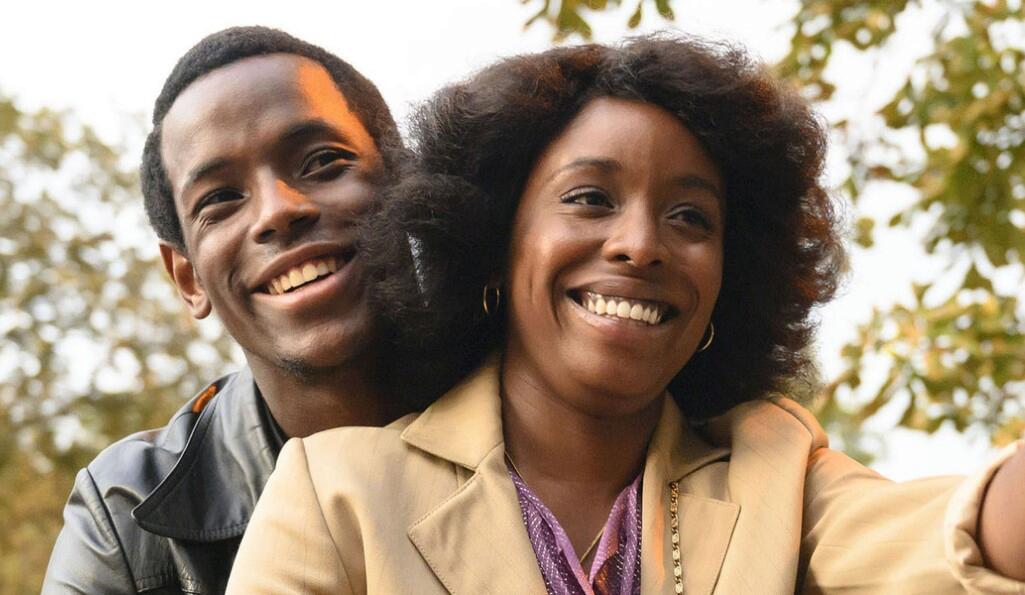

The latter half of the film focuses on a trial that garnered public attention and revealed the systemic racism both in the police and the judiciary. Written by Alastair Symonds and McQueen, the film occupies a relatively traditional courtroom drama, but infuses it with urgency and anger. It shows that in times of injustice just trying to live an ordinary life becomes a politically radical act. Lovers Rock by comparison is far less conventional and occupies the heart of the Small Axe anthology. Set in 1980 at a blues party in London, the film is an impressionistic and immersive ode to the music and passion of a counterculture. We see the deejays set up their equipment; the food prepared and the girls sneaking out in their party clothes. There’s an Altman-esque deftness in the gathering together of diverse characters, all with their own mini dramas going but united in this one place on this one night. McQueen is savvy enough to show that not all was peaches and cream. White youths gather as a potential threat; a police cruiser prowls and the sexual energy can spill into sexual assault.

But the music unites generations and sexes and in one wonderful instantly iconic moment Janet Kay’s Silly Games is taken up acapella and McQueen has the vision and the heart to stay with the moment so we end up not simply watching it, but feeling it too, through and through. If nothing else these films have at an instant doubled McQueen’s filmography. But more importantly for British cinema it has filled a gaping hole in the representation of the black experience. This achievement along with Michaela Coel’s brilliant TV drama I May Destroy You heralds (hopefully) a new more inclusive and diverse era in filmmaking. If that occurs Small Axe and Steve McQueen will certainly be marked as a key moment when voices were raised.

Leave a Comment