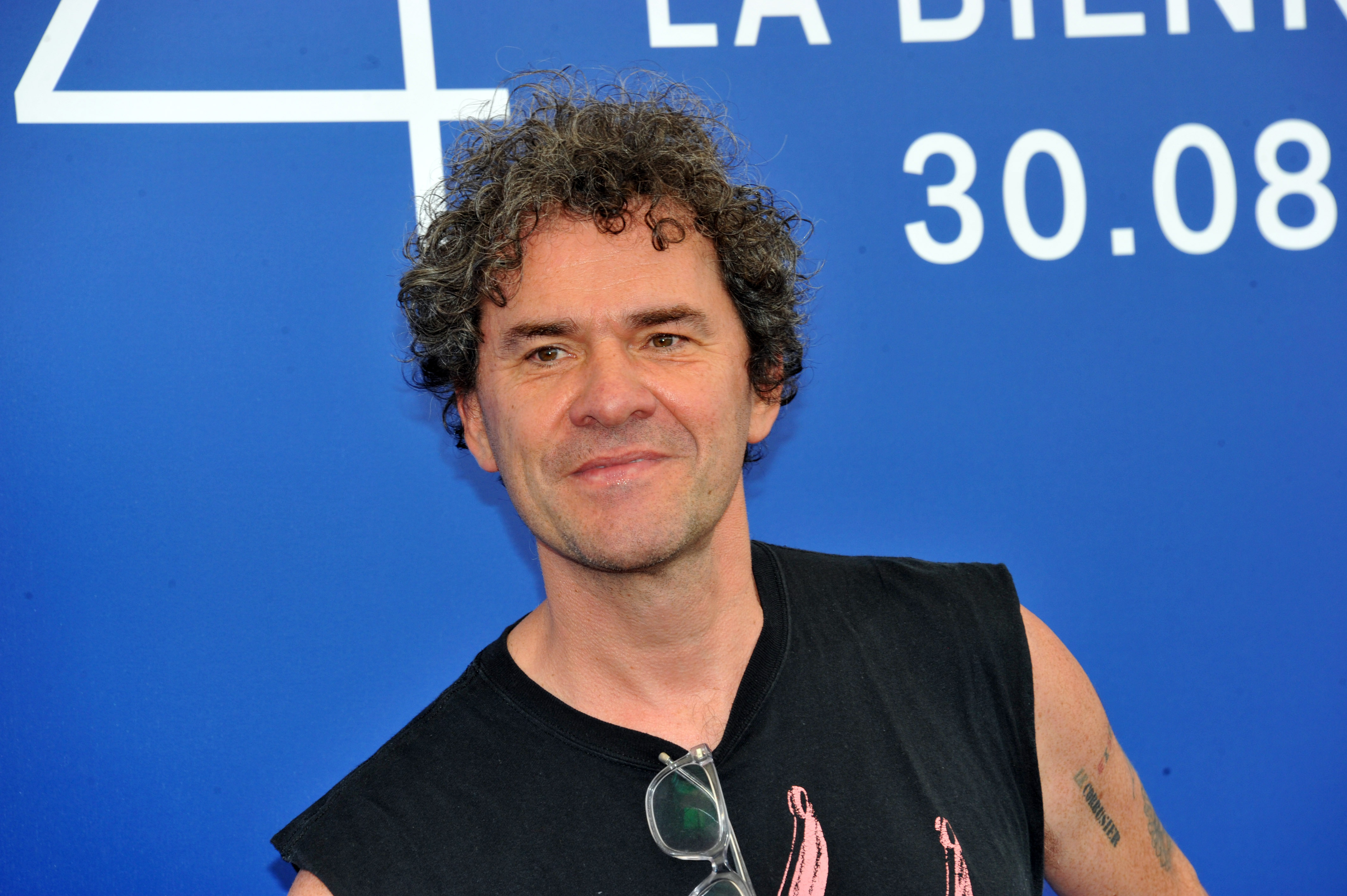

As film fans, we’re fortunate enough to be treated to a Mark Cousins documentary once every few months, such is the prolific nature to his work. Also as film fans, we were even more fortunate to be granted the opportunity to sit down with the Northern Irish documentarian over a coffee, and discuss his latest project The Eyes Of Orson Welles, where he takes the viewer on a journey into the mind of one of cinema’s greatest forces, through the drawings and letters he left behind. Cousins discusses his initial apprehensions about making this movie, what he would most love to discuss with – and show – Welles if he were still around today and why this film, at its core, was like a letter to his late father. He also goes on to discuss where Welles would fit in within a modern cinematic landscape, and on his next feature Women Make Film, where he has collaborated with Tilda Swinton.

So what compelled you to tell this story? Did the idea of making a documentary about Orson Welles come first, or did you hear about his collection of art first, and then realise there was a story to be told?

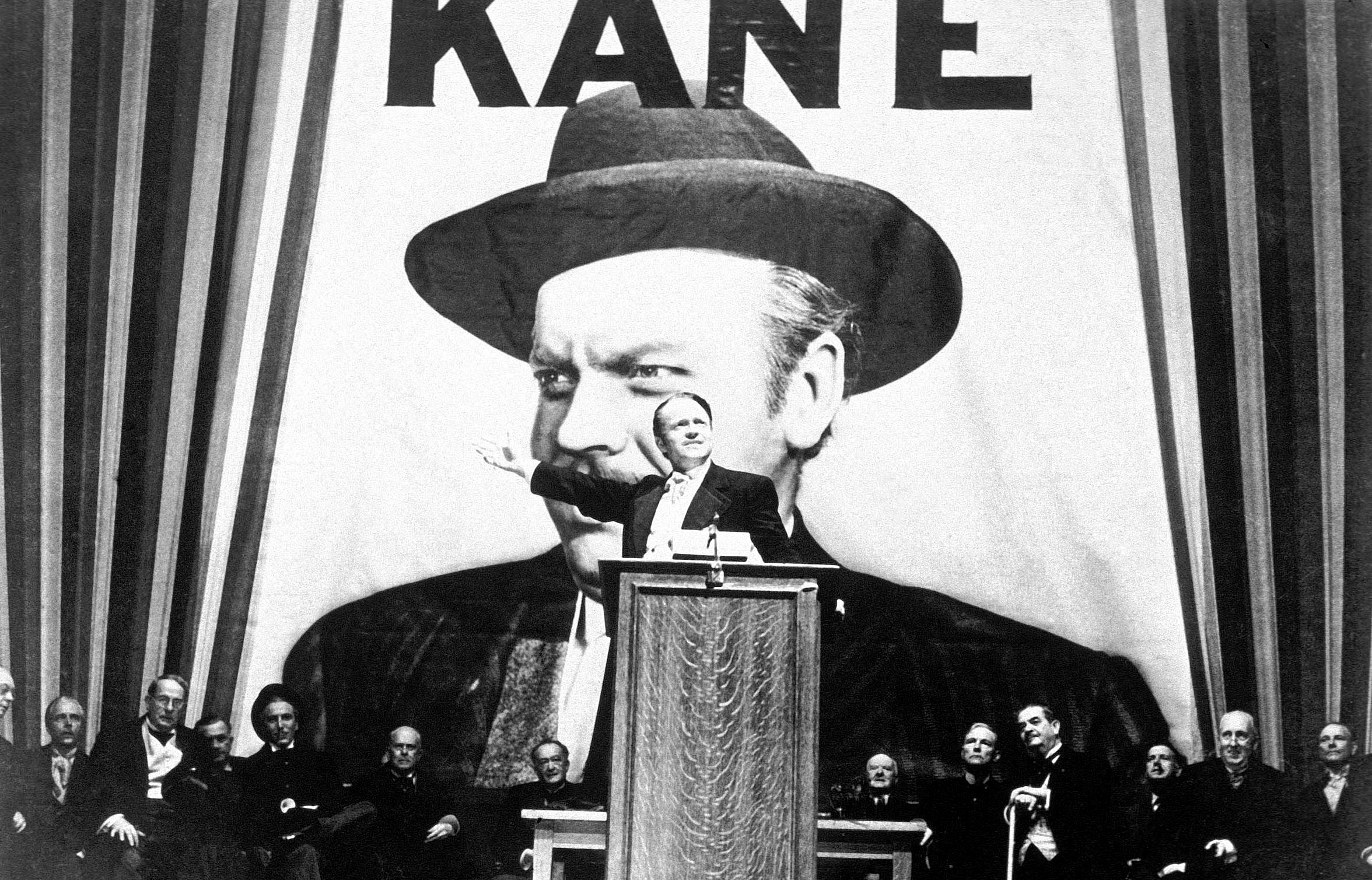

It was very much the latter, I didn’t want to make a film about Orson Welles. I admire him, but his place in film history is secure. I love doing things about African and Iranian cinema, so no, I didn’t want to make a film about Orson Welles. He’s such a colossus, it’s daunting to make a film about him. But then I met his daughter through Michael Moore and she told me about all of his drawings, and she knew my work which helped, and I quite quickly realised, when I saw the artwork, that there was something new here. Orson Welles didn’t have a diary, but it was almost like I had a visual diary. Like this one here for example [Cousins takes a drawing out of his bag that Orson Welles had drawn] – this is from around 1972, and look at the melancholic sky and at the drinker, you can see the unconscious mind of Orson Welles. People have often said that when people draw, especially when they draw fast, that they’re not thinking logically, they’re just expressing themselves in an irrational way, and that’s what we can get from these.

I went to The Beatles museum in Liverpool and despite all of the memorabilia and the guitars, etc, the thing that always stuck with me the most was seeing lyrics written down by John Lennon, there’s just something so intimate and timeless about seeing something they’ve physically put onto the page.

Yeah Leonardo Da Vinci called it the “changes of mind”. Scribbled down lyrics are changes of mind, and in these drawings from Welles you can see his mind ticking over. It’s so personal. It’s very intimate, that’s the word, and I wanted to make a film that was intimate too.

The narration is directed at Orson Welles, but despite the fact you ask him a whole myriad of questions, if he was sat here now, what would be the one, burning question you would most like to ask him?

I think if he was sitting here, first of all, we wouldn’t get a word in edgeways. He was a raconteur, he’d be talking to the whole room. The burning question for me, would be “What does it feel like to look at the world through your eyes?” We know that he constantly used that 18mm lens that made his films wide, and in those interviews he gave in French, he said that only did it because nobody else was doing it. In other words, there was something about the way this man looked at the world that was bulging and spacial. We know more about neurochemistry now and the perception of space and people are great at it, so I would actually love not to ask Orson Welles the question, but to put his brain under one of those MRI scanners and see where the visual cortex lights up. Which is a very technical answer to your question, but that’s what I would like to see, where that visual cortex lights up under a scanner.

There’s also a throwaway line in the narration where you discuss Groundhog Day and mention it that it was released a few years after Orson Welles died, but it got me thinking about all the films he missed. Is there one film you would love to sit him down and show him?

Yes. Yes, there are several, but I would love to show him Sokurov’s Russian Ark, the single-shot film. I think he would’ve loved that. He was a single-shot guy. I think that Orson Welles is the patron saint of GoPro cameras, even though they didn’t exist then. There was a brilliant documentary called Leviathan, shot with GoPros, about fishermen, which I loved, and I thought it was profoundly Wellesian. They are the two I would most like him to see.

I left the film feeling like I had such a close relationship with Welles. You must feel like you must have such an affinity with your subjects. If you were to watch one of his films now, would you realise that you have a different relationship than you did before you started this project?

Absolutely, it’s profoundly different. You’re looking for an intimacy. In fact, I have another thing to show you. [Cousins reaches back into his bag, and brings out Orson Welles’s old boot]. I bought this on an online auction. Look at the width of that ankle – he was a big man. Anyway, we need to take our heroes down off their pedestal, and someone like Orson Welles, who is a bit of a legend, I had to humanise him and turn him into a man for himself, so I could be intimate with him. A lot of films have a secret story, and the secret story in this film is that it’s really about my dad, who died very young, when he was 56. I had to do the eulogy and I stood up and found myself saying, “Dear Dad” and I spoke to him. And that’s what this film means, privately to me, it’s a letter to a dead dad. That gives it an emotion, hopefully, an intimacy and though I never met Orson Welles, it gives us the sense of loss that we have as film lovers, that he died when he was 70, which is too young. So that intimacy that you’re talking about, it comes from the idea of this being a letter to a dead dad. I didn’t tell his daughter that until the film was finished. She phoned me in floods of tears saying she was so moved, and that she’d never seen her father like this before, and I told her it was a letter to my dead dad and she said, “Oh my God” and then more floods of tears.

The narration is like a long letter – but what is your process? Do you sit down and write that in one sitting, as though it’s a screenplay?

I always write to picture. For me, the words never come first. I can see it in films when somebody has written something and then they’re looking for an image to illustrate the text, but that is back to front for me. So what I did with this film was to get all the artwork, clump them together on the themes you see in the film, and then put them in sequence and then I got an ironing board of all things in my flat, and laid them out in clumps. Then I could cast my eye over them and I could see the film, and I would sit each morning and write between 7.30 and 9.30, so for two hours a morning I would write to the image. Everything was quiet, there was nobody in my flat, and I was trying to really engage with the image and feel emotions with the image and then write that down.

How do you think Orson would fit into this modern world? Not just as a filmmaker, but politically speaking.

I say in the film that the world has become Wellesian, I think these figures, like Erdogan and Putin and Modi in India, and of course a certain Donald Trump, these are all almost creatures from Welles’ work, they’re larger than life, they’re dictators of some sort, they are empty vessels in some ways and echo chambers and that all fits very well. In terms of the politics of the film industry and #MeToo, etc, to his credit, he came from an era when men did act inappropriately, there has never been a single allegation made against him. Loads of lovers, of course, but never a single allegation of any inappropriate behaviour, and you think, thank f***. I think he was too good a man for that, and also the film industry has moved in his direction, so I think he would fit in very, very well.

As a fan, were you relieved to discover that there wasn’t any allegations made against him?

Absolutely. I went through the Polanski thing where I read all the quotes by Samantha Geimer who said it was appropriate to forgive because he had apologised and she had forgiven him. Then recently three more allegations came out, and he is moved back into an area where you think, I don’t like you very much. But with Welles there’s none of that. He wouldn’t have been fun to be in love with as he was in love with lots of people, and he hurt women, but even the women that he hurt, they loved him afterwards. I think he was a very loveable man. And what is loveable about him? If he talks all the time and he’s full of ego, what’s loveable about that? I think it’s the lust for life, the passion for being alive and living life at a hundred miles an hour, I think that’s a very attractive feature in a human being.

You’re obviously a big fan of his, I can see from your Orson Welles tattoo on your arm…

I’ve also got Welles written on my customised trainers. [Cousins lifts his leg up to show me a pair of Adidas trainers with Welles printed on the side].

There we go. Do you have to seperate the fan from the filmmaker when making a feature like this? Or do the two work in unison?

I think they’re the same thing for me. I think filmmaking is an expression of the feeling of being alive, and you can do it in all sorts of ways, documentaries or fiction films. So I’ve never ever believed in the separation between the subjective and the objective, I’ve never made films that have tried to be objective truths as it were, I’ve always been interested in the poetics of filmmaking and the subjectivity, so I’ve never felt the need to seperate. You don’t want to gush, of course, that’s a whole different thing. When I watch a film I watch it as a child and then when the film finishes I switch on my adult brain and figure out what that experience was, but I watch it as unfiltered a way as possible, to be as entranced by the experience as much as I possibly can.

You do have a very unique, romantic way of watching and speaking about cinema, but when you’re actually watching it, do you do so on those terms? Or is it afterwards you start formulating your perception?

You’re right to use the word romantic, I am a romantic. In terms of cinema, I don’t watch films as an intellectual, I don’t watch them as an academic, or a historian or a filmmaker or any of that stuff, for me they’re too narrow. I always sit in the front row, I want the screen right in front of me, I want it to be as big and overwhelming as possible, I want to feel as though it’s like sitting under Niagara Falls, I want to feel the spray of cinema on my face. I’ve always wanted that.

I loved that moment in the film when you get that box full of Orson’s drawings and artefacts and I could feel your enthusiasm. Was there a particular letter, or painting, that overwhelmed you the most?

It’s the drawings of tears. Welles drew pictures of himself crying, there was a lot of sadness in his life because of some of the terrible reviews, and he remembered them all. I think we think of him as a king-like figure, but there was a sadness to his life as well, he regretted how much he hurt the women, and the men, in his life. In that box I saw some of that pain and it touched me.

Next up you have Women Make Film, which is a 16 hour endeavour. What can you tell us about that one at this stage?

Not too much. Ir’s exec-produced by Tilda Swinton and she’s voicing the first four hours and she’s done a beautiful job. It’s not a history of women in cinema, it’s almost like a film school where all the teachers happen to be women. What’s startling is how many of these women we’ve never heard of. That’s the revelation in this film, we think we know the great women directors in history, but we really don’t.

It’s quite striking how few female filmmakers are at Venice this year. Is there to be blame attached to the Venice Film Festival for their programming? Or is the issue more ingrained, emblematic of an industry that simply isn’t giving women the chance to make movies in the first place, meaning there isn’t an awful lot to choose from?

There are a number of issues there. We need more women choosing content, if there were more studio bosses that would be one thing. However, some of the most powerful studio bosses have been female and one in particular – how many female directors has she hired? Zero. So there’s that. There’s also the broader culture, if you think of Italian culture it’s quite macho, it’s not totally Venice’s fault, because Italy, which has over-achieved in cinema for a country that size, it’s had a lot of great directors, but there aren’t many women in there at all, so it’s the film industry’s fault. Liliana Cavani and Alice Rohrwacher recently, but there aren’t as many as there should be in a film culture as successful as that, so we have to point the blame at anybody who is any part of the system who hasn’t tried to change it, they are part of the problem.

You’re an incredibly prolific filmmaker…

Three this year.

Exactly. Is that just the nature of your work – do you just love to keep busy? Because I do get the impression that for you it doesn’t feel like a job, it feels like a passion. Is that what makes it never-ending?

Yeah, I’m unstoppable. My phone told me it would take 43 minutes to walk here and it took me 31. I do everything very fast, even filmmaking, you know. I do get tired, and particularly I have a problem with jet-lag so that’s an issue for me, but otherwise I just love making stuff. This morning I was approving the sound mix and the poster for a new film. I am energised by filmmaking and you’re quite right to say that it’s a passion, I never use the word ‘professional’ about myself, I’ve never thought of myself as a professional, I’m an amateur, and that means that if what we do is close to playing, and filmmaking to me feels like playing, then it’s never to be resented. I need to take a break, but I just love doing it. As well as doing three films this year I’ve also released a book. It’s crazy, but I love it.

The Eyes of Orson Welles is out now.

Leave a Comment