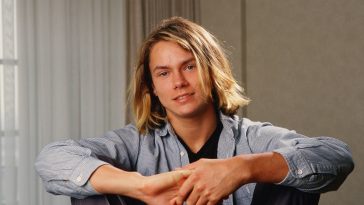

Back at the Toronto International Film Festival we had the pleasure of sitting down with two real forces in the industry – chatting to Michael Winterbottom and Dev Patel on their new film The Wedding Guest. Patel talks about his role as producer on the project, and what it was like playing a shady character, which presents something of a departure for him. He also comments on how he is learning about his own heritage through roles he plays, while the pair also discuss their own thoughts on the way violence is presented in film.

Dev, you’re producing this film as well, what’s it been like being more involved than usual?

Michael Winterbottom: He’s the boss.

Dev Patel: Nothing really changes.

So what attracted you about this story that made you want to produce?

DP: What attracted me was Michael, I really wanted to work with him. When I read the script it reinforced my distant opinion of him, which is that he’s a cinematic chameleon, and this in itself is so different, how the hell did he pull this out of his brain. It was time constraints really, I was going off to do something and I didn’t want to miss this opportunity to work with him, and sometimes when there’s a project sent there’s a momentum behind it, an energy you don’t wanna dissipate. So I asked where the film was at and Michael said he’d just finished the script, so I asked if we could work at it together to get it pregnant so we could go and shoot it within a month, and it happened. The rest of it is just me learning my lines and being told what to do, as any other actor really.

Dev has a very likeable screen presence and often gets cast as nice people as a result. So why him for this role? Because there’s a dark undercurrent to this character.

MW: I’m a huge fan of his work, that’s the main thing. But it’s really about two people and the first part is all about Dev, trying to figure out who he is and what he’s doing, and we had to have someone who could really hold the screen and Dev is brilliant at that. For me, he’s not unlikeable, I wanted a sense that he has his job to do, and he’s doing his job, I didn’t want him to be the bad guy at all. But obviously there is a tension because we don’t know what his motives are, and we don’t know what is going to happen. You start with the question, who is he? Then the question keeps shifting and every time you think you know what’s going on with him it just shifts a little bit each time and by the time you get to the end you move away from the starting point. There’s only really two people in this film, you’re going to want to watch them for 90 minutes. He’s character doing his best, no matter the morality of what he’s doing, he’s someone with a plan and once that plan is taken away from him, he’s trying to work his way through what to do next and being sympathetic is good.

Was it fun playing someone a bit darker? Someone with so much mystery attached.

DP: That’s what we wanted, sometimes films run the risk these days of making a point and then smashing you round the head with it ten times. Actually, audiences are really clever and we’re trying to make a piece of art here that is delicate and sometimes those emotions that are deemed abstract, we want you to come away with something different from everyone else, and to then want to talk about it afterwards. It’s a man who is very composed at the beginning and as his plan becomes more and more complicated you see tiny little micro-tears start to occur and then there’s these constant shifts of power in the film that are done very subtly, which could be in a kiss, and all of a sudden the person who’s in charge is no longer in charge. One moment she’s just a girl being flung around like a piece of luggage, the next she’s far more in control of the situation, so you’re watching this trying to figure out this mental chess game that is going on between them, as they’re trying to figure each other out also.

What is about India and the sub-continent that keeps drawing you in, Michael?

MW: When you go to India there is so much going on, so much life and energy, it’s attractive from that point of view, when you’re filming there the streets compared to a streets in the suburbs of London, there’s a lot more energy. The starting point was when working on another film in the Punjab and we talked to these guys who had been to their friend’s wedding. In a way when you work somewhere it can often generate ideas for another film. So having worked in India once, Pakistan once or twice, you get another idea and end up going back. So it’s not really a conscious thing, it’s just that when you’re there it can be a starting point for a story you come back to.

Dev has just called you a chameleon, do you agree, and where does that inclination to keep trying new things come from?

MW: I don’t know, I think generally I just try to make films very simply, and there’s an element of observation in most of the things I do, and a lot of road movie elements in what I do, but each story has its own requirements and in this case it’s really about two people, so my approach was to try and record that. They don’t say much to each other, so it’s very much about the mood between the two of them, and you imagine how they’re feeling about each other, rather than be anything specific in the script or the story, it’s just two actors in a room, in a way.

Off the back of The Trip, where you let Rob and Steve improvise, what was it like reverting back again to what I assume was a more structured piece where actors had to stick to script?

MW: In terms if dialogue, it was a very short script with very little dialogue. When we started I wasn’t sure how much improvising we should do but it was more interesting not to add to the dialogue, so it is improvised because there’s not much in the script, it’s very thin. Dev and Radhika were improvising their relationship, I wanted to see what happens with the two of them.

Dev you’ve shot so many films now where you character has to go to India, or film’s entirely set in India. Have you found through acting you’ve learnt more about your culture and history than you would’ve perhaps otherwise?

DP: Absolutely. Otherwise I’d only ever be going to India for weddings, though I guess in this I was kinda doing that. But yeah it’s allowed me to really understand a part of my heritage that I’d never really been able to see. Slumdog really introduced me to India in a big way and ever since I keep going back there and I’m constantly fascinated and surprised and baffled every time I go. I just finished writing something which is based there. It makes me understand my grandparents better, it makes me understand my mum and dad better, it’s the stories that make up my DNA. So I’m just very lucky to have been given stories like this, where we don’t need to pin it on some massive big event so it can pass through a studio system, or validate it in some subservient way. It’s actually just about two people, and it’s an interesting relationship story and the fact that this movie can be made and be financed and people turn up to see it, is an amazing progression and this wouldn’t have happened a couple of years ago. In its simplicity is its power, that we can tell this type of story, and have two brown faces on screen, it’s like a quiet victory I think.

You’re very convincing in the film with weapons – what with this and Hotel Mumbai as well, what’s your relationship like with violence in film and how it’s portrayed?

DP: I hate guns, man. When I get put one in my hand, underneath me I’m terrified of this thing in my hand, this killing machine, it scares me and to try and maintain composure with that thing is hard. Michael could see it, I was a bit more panicky on those days. Look, I grew up watching Bruce Lee movies, I can’t tell you that I understood nuanced cinema when I was a young child, I snuck downstairs and watched Enter the Dragon and thought it was fucking amazing. Then I watched all the Schwarzenegger films, and watched everything in between those two worlds. So I enjoy it, I did martial arts for ten years when I was a kid, and I like it, I love martial arts, all the old kung fu movies, and newer films like The Raid, shot on micro-budgets. And I like what Tarantino does too, I think there’s a lot of filmmaking in it, and I unfortunately we live in a violent world, you’re seeing people pulling triggers in hotel rooms, talking of Hotel Mumbai. Teenagers just walking into train stations and killing fifty people with the squeeze of a trigger, and injuring a hundred. There’s a difference between the art of martial arts and senseless violence, and when I was trying as a martial artist I understood that when I was doing it. So what we do as filmmakers is try and reflect reality as best we can.

I was interviewing Gaspar Noe recently, and he said his film Love was banned in places around the world because of its explicit sexual content, whereas Climax wasn’t, and that’s quite violent. It’s weird that violence is considered to be a lesser of the two taboos. Michael you did 9 Songs which was quite graphic. Is that the wrong way round?

MW: Yeah definitely. There’s no reason why sex should be banned, it’s something in the world that we want, whereas violence is something that we don’t want.

Michael you made your debut in 1989. So now looking back over 30 years, any highlights?

MW: There’s no highlights whatsoever, apart from working with Dev – this is the highlight!

DP: Get outta here.

MW: I don’t really tend to look back.

DP: What’s your favourite of your movies, Michael?

MW: This one. No, the next one.

What is the next one then?

MW: I’m doing a thing with Steve Coogan, a comedy about a retail fashion billionaire who throws a party for his 60th birthday.

Leave a Comment