The most famous scene in David Lynch’s 1980 film The Elephant Man takes place in Liverpool Street railway station in London. John Merrick (John Hurt) is returning half dead from Europe, having escaped his alcoholic and abusive “owner” Mr. Bytes (Freddie Jones). As the masked figure limps through the station, Merrick is accosted by a child with a pea shooter shouting: “Mister, why is your head so big?”. A little girl is accidentally knocked over and Merrick is unmasked and chased into the toilets by a mob. Cornered, he turns on the crowd and cries despairingly: “I am not an animal! I am a human being. I am a man.” Merrick’s plea is to be recognised as human, rather than as a freak.

The scene echoes the opening of Richard Lester’s recreation of Beatlemania in A Hard Day’s Night (1964) with the Fab Four being chased by fans through another London station (Marylebone). The baying crowd of Victorian rubberneckers and the adolescent Beatle fans might seem a world apart but as John Lennon grew disillusioned with performing, he would refer to their final American dates as “just a sort of freak show.” In more recent years, reality talk shows such as The Jerry Springer Show and in Britain The Jeremy Kyle Show have frequently been criticized as modern day freak shows, opportunities to gawp at the outlandishness of other people’s lives. The latter was pulled from the air following the suicide of a participant of a show.

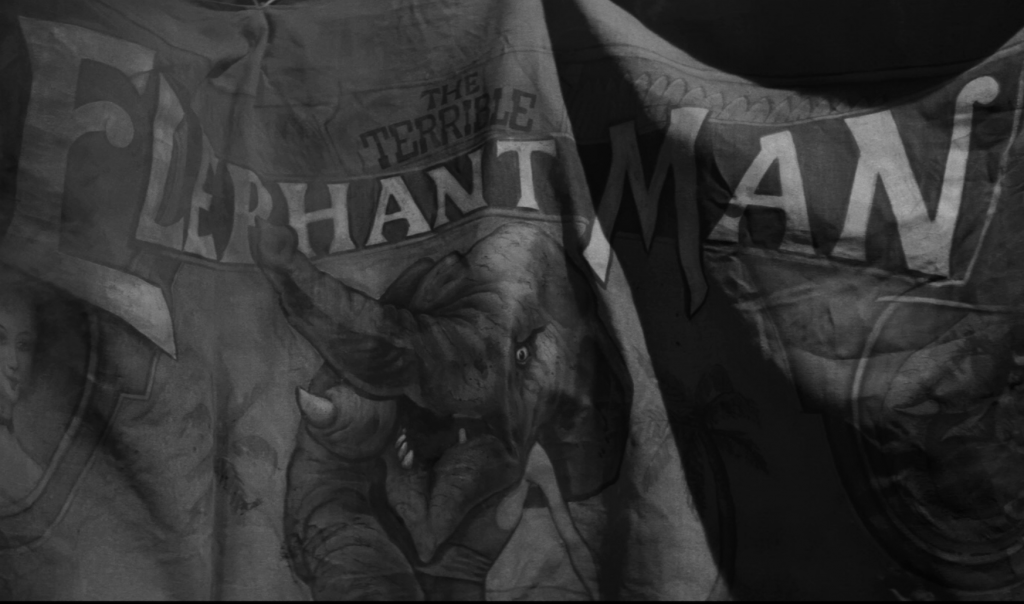

David Lynch’s film is a sympathetic attempt to humanize its protagonist, but as with Tod Brownings’ 1932 shocker Freaks, it is difficult to portray a freakshow without becoming one. The tension can be seen on the film’s poster where the tagline uses the “I am a man” quote below the title of the film, which seems to contradict the assertion. Celebrity always seems to be a form of erasure of the actual person. Che Guevara becomes a t-shirt: Marilyn Monroe, a poster. It’s a cultural application of Heissenberg’s Uncertainty Principle: looking at people changes them. There is a lot of looking in The Elephant Man. Dr Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins) first encounters Merrick as a punter granted a private show by Mr Bytes, the malign carnival barker. We as an audience first see other people looking, registering the monstrous via the reactions of his audience, whether it is horror, disgust or Dr Treves’s single tear of pity.

From the exploitation of the freakshow, Merrick graduates to medical curiosity and finally a darling of the high society, led by Anne Bancroft’s actress Madge Kendall, and even receiving Queen Victoria’s recognition. As Merrick’s star rises, Dr Treves plays the role of Professor Henry Higgens from George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, rescuing John, protecting him, coaching him how to speak and turning him from a brutalized victim into not only a gentleman but something of a dandy. The release of the film was both a commercial and critical success. At the Academy Awards it was nominated for eight awards, though it failed to win any, losing out to Robert Redford’s antithetical Ordinary People. As the years have passed, it has remained a firm favourite.

Bradley Cooper, who made his own Pygmalion film with A Star Is Born, credits the film with inspiring him to become an actor and played the role of John Merrick on Broadway. The Elephant Man remains a powerful and moving film. The black and white victoriana makes it an almost timeless piece. The attitudes towards disability and deformity might lean towards the mawkishly patronising at times – Merrick’s receives an ovation at the theater for simply being the Elephant Man – but David Lynch never allows us to forget as an audience we are not just watching, we are also staring. Dr Treves has the self-awareness to realise that he is not so different from Mr Bytes in his exploitation of Merrick. “Am I a good man or am I a bad man?” he asks his wife, simply. It is a question we as an audience must also face. Are we watching with genuine humanity, or are we simply asking: “Mister, why’s your head so big?”.

Leave a Comment