Several months before One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest would fully solidify Jack Nicholson’s Hollywood reputation and lead him to Oscar glory in 1975, the actor opted to appear in the lead role of renowned Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni’s third English language film, The Passenger (a film which is currently enjoyed a big screen re-release here in the UK). Although it wasn’t unheard of seeing big American stars lending their talents to the work of singular European auteurs – Burt Lancaster had appeared in Visconti’s The Leopard a decade earlier, while fellow A-lister Donald Sutherland would play the lead in Fellini’s Casanova the year following – The Passenger was a notable change of pace for Nicholson, and certainly required the actor to dial down those distinctly ‘devil may care’ mannerisms of his.

However, Nicholson is never less than magnetic here, and despite the film’s languid pace and discernible lack of drama – dialogue is kept to a minimum and there’s no score to speak of – it manages to pull you in from the very start and doesn’t let go. The Passenger is both a compelling and pensive character study, and in a sense it almost comes across as an anti-thriller, despite pulling from tropes usually associated with a genre picture. In the film’s opening scenes we’re witness to Nicholson’s TV journalist David Locke, who looks like a man completely adrift (literally and figuratively) as he’s traipsing around the Sahara desert in search of interview subjects from a nearby civil war.

His Land Rover getting hopelessly stuck in the sand dunes – which inspires a mini outburst with only the vaguest Nicholson-like freak-out anywhere within the film – seems to be the last straw, and Locke slumps back to his barren hotel, defeated. Chancing upon the body of a fellow guest he has become briefly acquainted with, he decides to assume the dead man’s identity. In a quaint and decidedly old-school pre-Jason Bourne move, he simply uses a scalpel to remove and swap his passport photo with that of the deceased man, whom he bears a slightly resemblance to.

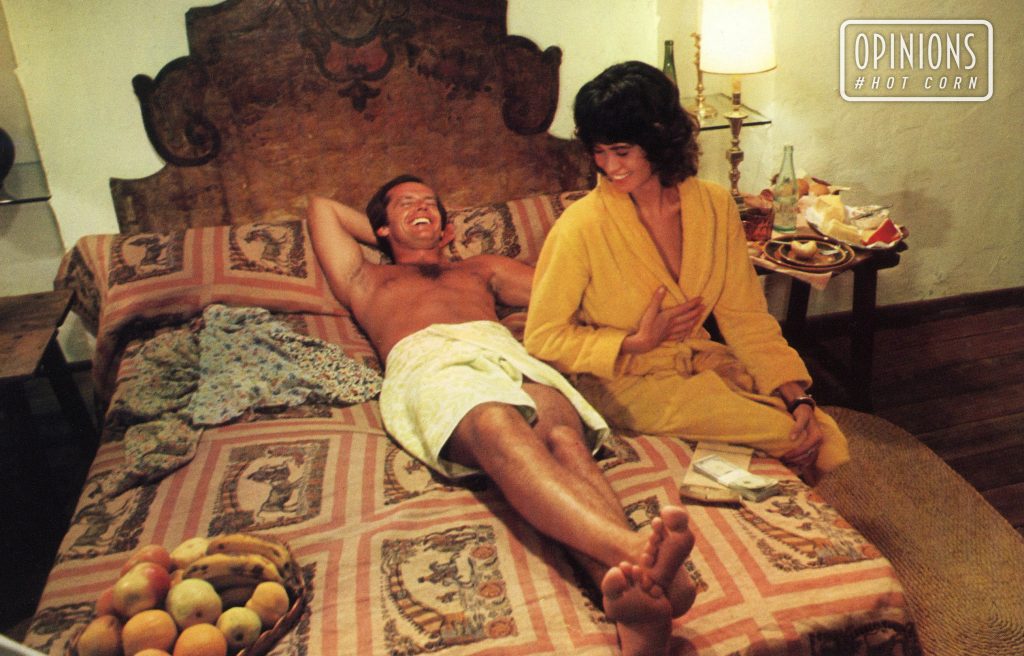

Thus begins a journey for the imposter – which largely takes place around Spain – and with a new young beau by his side (Maria Schneider – a few years before her infamous run-in with Nicholson’s buddy Marlon Brando in Last Tango in Paris). It isn’t long though before Locke begins to question both his decision to abandon his life and family, and ultimately if the shoes he’s filled are actually safe for him to be in. The Passenger is a film which has rightfully grown in stature over the years, and it was even Nicholson himself – in a shrewd moment of cultural foresight – who initially bought the rights to Antonioni’s film to ensure that it would remain intact and available for future restoration and appraisal.

The film’s central premise and that idea of turning your back on your old life to begin a new adventure is undeniably a tantalising prospect, and you can certainly see it’s influence in the works of contemporary filmmakers, some less obvious than you’d imagine. For instance, Spielberg’s underrated 2005 historical drama Munich – set around the time when The Passenger was actually made – is peppered with quieter, reflective moments which feel directly indebted to Antonioni’s stripped-down style, and this film in particular. The Passenger’s pièce de résistance occurs at the end, where a 13 minute unbroken shot slowly takes the viewer through the barred window of Locke’s hotel room and into the dusty forecourt where small and seemingly inconsequential moments occur until the fate of the character is finally revealed as we loop back to face his room. It’s a scene which in a modern film would be screaming ‘look at me’ yet here is completely in tune with Antonioni’s formalism and manages to be a bravura piece of filmmaking without drawing attention to itself. That in itself is an accurate summation of the entirety of The Passenger.

Leave a Comment