In 1995, the world cast its eyes upon a piece of film that shook it to its core. A 17-minute grainy segment of grainy, black and white footage purportedly depicted an autopsy being undertaken on an extraterrestrial recovered from the 1947 flying saucer crash near Roswell, New Mexico. The film went loosely by the name alien autopsy. During promotional duties for the 2006 Ant & Dec movie of the same name, and based on the saga, the owner of the original, Ray Santilli, sheepishly declared that his much-disputed and apocryphal 1995 work was a ‘restoration’ rather than a fake. 24 years on, it still stands as what could potentially be one of the grandest hoaxes of all time.

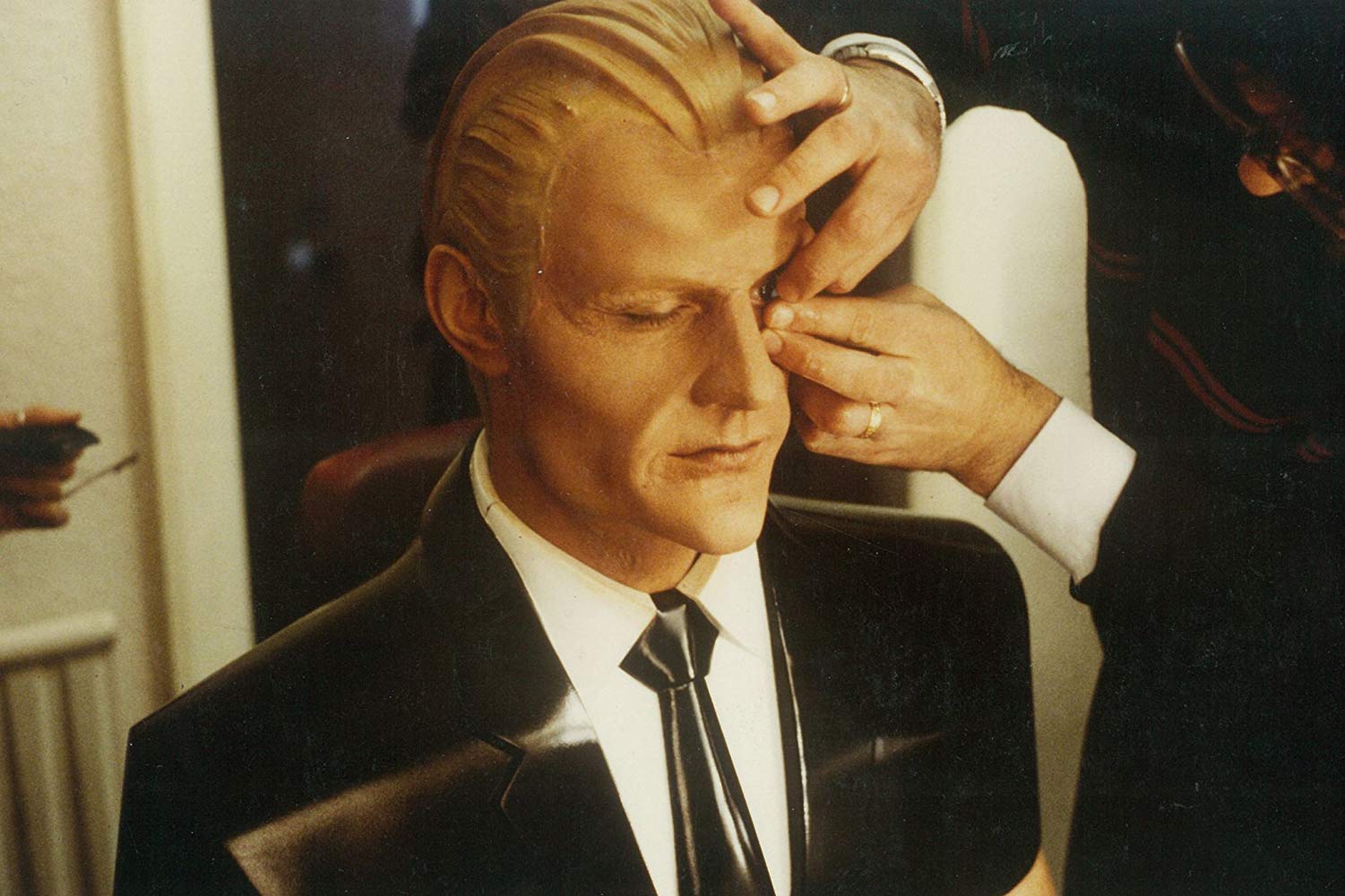

The man responsible for (re)creating the alien was uber-talented, British fine art sculptor, John Humphreys. His is a resume loaded with notable film and TV credits, having worked on Doctor Who, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and the Young Ones, to name just a few. He also boasts quite the portfolio of work outside of the world of cinema. Humphrey’s work was also recently included in the Opera Gallery’s Beyond Reality exhibition. With fascinating insight, eloquence and articulacy, he spoke to the Hot Corn and laid bare his methods, his feelings on the film industry and how he turns ‘the onlooker into the artist’. For an arresting peak into the workshop of a prosthetic master who bends and manipulates our view of reality, read on.

How would you summarise your work?

«My approach is looking beyond what we see. When you see a picture of my work, it looks like a distorted image, but when you see it in 3D and in real space, it looks neither like a three-dimensional object nor a two-dimensional object. It hints at a fourth dimension».

How so?

«What it is, is your brain is trying to correct the vision that your eyes are giving it presuming that something is not quite right. It struggles and struggles and struggles to figure it out, during which time you are completely stuck with observation as you try to figure out what is going on.

Instead of giving people an answer, I’m giving them a question. What I am doing is turning the onlooker into the artist».

Is that an accidental by-product of your life’s work?

«No, what happened was, many, many years ago, I was a part of the film club at the Cheltenham Art College and I used to be quite interested when they used to use the distorted, stretched images for the opening sequences for Spaghetti Westerns before they used to revert to reality. That always intrigued me».

Do you remember first fulfilling something that evinced this concept yourself?

«I did Max Headroom, who was the first ever computer generated tv presenter – but he wasn’t actually computer generated, he was made with prosthetics. Ironically, it won a BAFTA award for Best Graphics (1986)!

When we did the make-up test, I distorted the image of the sculpture part of it. It played mind games with people’s eyes. It looked like a computer-generated image before there were computer-generated images. Yet, I knew there was something more interesting than that, but no one could see it, so I started developing my own fine art work to explore that area of disturbance to the mind».

Looking at your work, it does seem to allude to that disturbance most effectively.

«When onlookers look at my work, they have to start using the spatial part of their brain and manipulate three-dimensional space and turn it into reality. So people come and look at my work for ages. They don’t just walk away. And if you’re going to create art, you want things to arrest people. That’s the objective side of it.

The subjective side of it is trying to express how you see the world when things are altered for you in reality. We’ve all experienced bereavement and, if you’ve been unlucky and been in, say, a car crash or something. When you’re in that state of shock you see things in a different way temporarily, sometimes permanently. Your sense of reality alters and that sense of isolation from reality, that is part of the expression that I’m trying to convey in my work».

How do you go about your sculptures?

«I make my sculptures in clay or modelling wax and once you have the model exactly how you want it, you make a special rubber mould of it. It’s all coated in rubber and then that’s coated in two parts by fibre glass, so that you have a rigid mould that’s flexible inside. I cast the fibreglass inside into that mould and because you have the case, you have the rubber that comes off the fibreglass. You replace the clay with fibreglass and paint that».

What about a window into the subject itself? How do you get into that?

«At the moment, I’m doing one on Marilyn Monroe. I’m looking at millions of pictures and interviews to try to get to know her. It’s funny what you can glean from a person’s look, interview/spoken word. Little things make a big difference. It’s being intuitive. It’s like the alien autopsy, the Roswell thing. Again, my colleagues had some very poor-quality imagery and I interpreted that and dragged it out and turned it into a reality».

How long did it take you to make the alien autopsy film?

«Alien autopsy, including filming as the surgeon and all the effects took about 6 or 7 weeks. I then appeared as the surgeon in the Ant & Dec Alien Autopsy film as well, and that took about the same amount of time. As soon as we had done the first film, I just knew that we had created an iconic image».

What is a typical sort of film-based instruction?

«It depends. I worked on Alexander (Oliver Stone, 2004) and I was given a picture the size of the postage stamp of a piece in a museum, fuzzy and they would say, ‘I want you to make a Dionysus. It has to be 4 ft high and we want it in 3 weeks. See you later!’ Somehow, you look at the image, and you just manipulate your mind to visualise and make it».

What about your work on Charlie and the Chocolate Factory?

«Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was just something I did because I was a bit short of dosh at the time. The boss came up to me and said, ‘here’s a humbug sweet. Make me a 15ft humbug tree and make it funky’. And walked off. Then you put your heart and soul into making a surreal humbug tree: you visualise it and make something unique… I guess I’m just never comfortable working on films».

There must be some positives being associated with big films?

«To be honest with you, when you’re employed to work on a big film you’re a technician, although you might make lots of interesting things. Alexander was interesting to work on because it was a fantastic mental exercise. I had to be really disciplined and make fast, figurative, sophisticated pieces for the best part of a year and it was like going back to art school in 1900! People might mock this or decry all this now, but it doesn’t half develop the spatial department in your head!»

To find out more, visit www.johnhumphreyssculpture.com

Leave a Comment