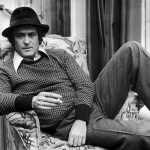

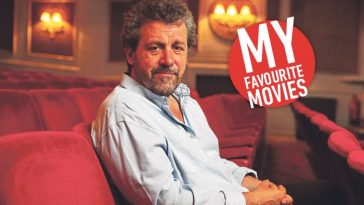

Nicolas Roeg was one of the most original and distinctive filmmakers Britain would produce. He claimed that he began in films solely because there was a studio across from his family’s home in London. He worked as a cinematographer on the 2nd Unit for David Lean in Lawrence of Arabia, before being promoted to the main unit for Doctor Zhivago. It was a sign of his growing confidence that he argued with Lean and ended up booted from the project. He worked with John Schlesinger and Francois Truffaut and photographed Roger Corman’s most beautiful Edgar Allan Poe adaptation The Masque of the Red Death in 1963.

During the 1970s, Nicolas Roeg moved into direction and went on a streak. His first film Performance, co-directed with screenwriter Donald Cammell, was pitched as a swinging 60s comedy but turned into a weird punkish tale as London gangster James Fox hides out in the London mansion of Mick Jagger’s dissolute pop idol and the two begin to meld. This was followed by Walkabout, a coming of age story that featured Jenny Agutter – the same year as she appeared in The Railway Children – as a young schoolgirl who with her brother is guided through the Australian outback by David Gulpilil after almost being murdered by their suicidal father.

In Don’t Look Now, Roeg made one of the most emotionally successful horror stories. Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie are grieving parents who on a trip to Venice are haunted by the vision of a little girl in a red coat. In 1976 Roeg adapted Walter Tevis’ novel The Man Who Fell to Earth and provided David Bowie, perfectly cast as the debonair alien who finds himself on Earth trapped by the gravity of excess, with his most successful screen role.

Each of these films blended daring experimentation that pushed the boundaries of the popular genre they inhabited. They were deeply human films which portrayed a world that was fragile, cracked, messy and uncertain – tables get knocked over, violence is random, things spill and smash – but there was always the possibility of love and connection. Whether it was loving the alien, or the beautiful eroticism of Sutherland and Christie finding each other again, a sex scene that’s more truly described as a love scene. There would be other great films. Bad Timing is an excruciatingly honest depiction of a toxic relationship coming to pieces, starring Art Garfunkel and then wife Theresa Russell. Another largely unsung masterpiece was Eureka in 1983. It stars Gene Hackman as a gold prospector in a chronicle of a death foretold that anticipates There Will Be Blood in depicting the corrosive effects of wealth and power on a pioneer.

There would be other films – Track 29 and Insignificance – and a brilliant late foray into children’s films with Roald Dahl’s The Witches, bagging another genre. But with British film increasingly divided into wannabe Americans, prissy prestige period pieces and the equally narrow austerity of social realism, Roeg didn’t ever quite fit in. To his credit. An uncomfortable talent, he was a spiky explosion of daring and experiment: a truly unique artist who should stand as a model of just how far an artist can go and the bravery of actually going.

Nicolas Roeg died at the age of 90.

- From Performance to The Witches you can watch Nicolas Roeg’s movies on CHILI

Leave a Comment