Our first social club gathering of 2019 seemed like the perfect opportunity to reflect on a select group of films that turn the big 5-0 this year. Nineteen sixty-nine is significant for many reasons, from Altamont and the end of the hippy movement to Bryan Adams getting his first six-string. As it turns out, there were some pretty great movies released that year. So, without further ado, what’s your favourite movie from 1969?

Stefan Pape – MIDNIGHT COWBOY

When casting our eyes back the 50 years to 1969, there’s no better place to start than with the Best Picture winner at the Oscars, John Schlesinger’s classic Midnight Cowboy. Ahead of its time – just – it’s imbued with a distinctive creativity prominent in 1970s cinema, in films like Apocalypse Now, while at the same time offering a profound take on the notion of the American Dream. That said, New York glistens in the movie; it’s a love letter to the city, albeit a somewhat upsetting tale that is surprising moving, given the quite playful tone. But it captures the essence of the city, and Jon Voight is exceptional in the lead, with a contagious, blissful demeanour. As for Dustin Hoffman? I mean, where do I start. Only thing I would say though, is that given his reputation as a method actor, I do fear he may not have actually showered for weeks. But hey, if it helps the performance…

Greg Wetherall – KES

Barry Hines’s A Kestrel for a Knave was thrust into my palms in English when I was at secondary school. Try as I might though, I could not connect with it. A little later – a little wiser and a little older – I obtained a tattered old VHS of Ken Loach’s film (itself only released a year after the book’s publication) and the melancholy that had failed to strike a chord on the page radiated warmly onscreen. I admonished my younger self as an immature philistine. How could I have missed the dolorous poetry? How could I have overlooked the affecting sorrow? Post-Thatcher, it was also now a window into a northern Britain long gone, with communities decimated by the ruthless obsolescence of the mining industry. It is not perfect; Kes bears all the hallmarks of a fledgling filmmaker finding his feet. The fade-outs are clunky and some scenes would benefit from judicious editing. And yet, this most British of films contains a dose of humanity that is so universal and timeless that it reverberates down the ages and beyond the confines of a specific culture. Well done Loach. Well done Hines. Thank you both.

Jo-Ann Titmarsh – BATTLE OF BRITAIN

Remember when you weren’t ashamed of being British? When Britain was synonymous with great humour, music, subcultures and fair play rather than a hostile environment, austerity and Brexit? Well, films like Battle of Britain helped to instil a sense of greatness (and superiority) into the general national psyche. Its stellar cast boasts just about every famous British actor working at the time. It has an actual burns victim and WWII survivor in Warrant Officer Bill Foxley (an advocate for burns victims after the war). It offers a pretty accurate account of this monumental battle. It has actual Germans playing Germans. And at the end of the film, as the credits roll, it lists every nation involved: a battle won not by the Brits, but by a coalition of nations coming together to fight fascism. 1969 is the year that negotiations began for the UK to finally join the European Economic Community.

Mark Grassick – BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID

At times it feels like my career as a writer is articles about Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid punctuated by other less important things. My love affair with the film began around 2002, when I happened to catch it on TV one night. Road To Perdition had ignited an obsession with Paul Newman and this just cemented it. I went into Tower Records in Dublin the next day and bought the DVD for £20, which even then seemed an extortionate price. It’s hard to think of another film that works so perfectly on so many levels. Newman, Redford and Ross are all sublime while William Goldman’s script dances between comedy, pathos and action like it’s waltzing on air. It’s an unusual beast too, in that there’s no tangible villain. Sure, there’s the ominous, distant presence of Lefors and his relentless posse, but the real baddie is time, an unstoppable force that will catch every man, hero and villain alike.

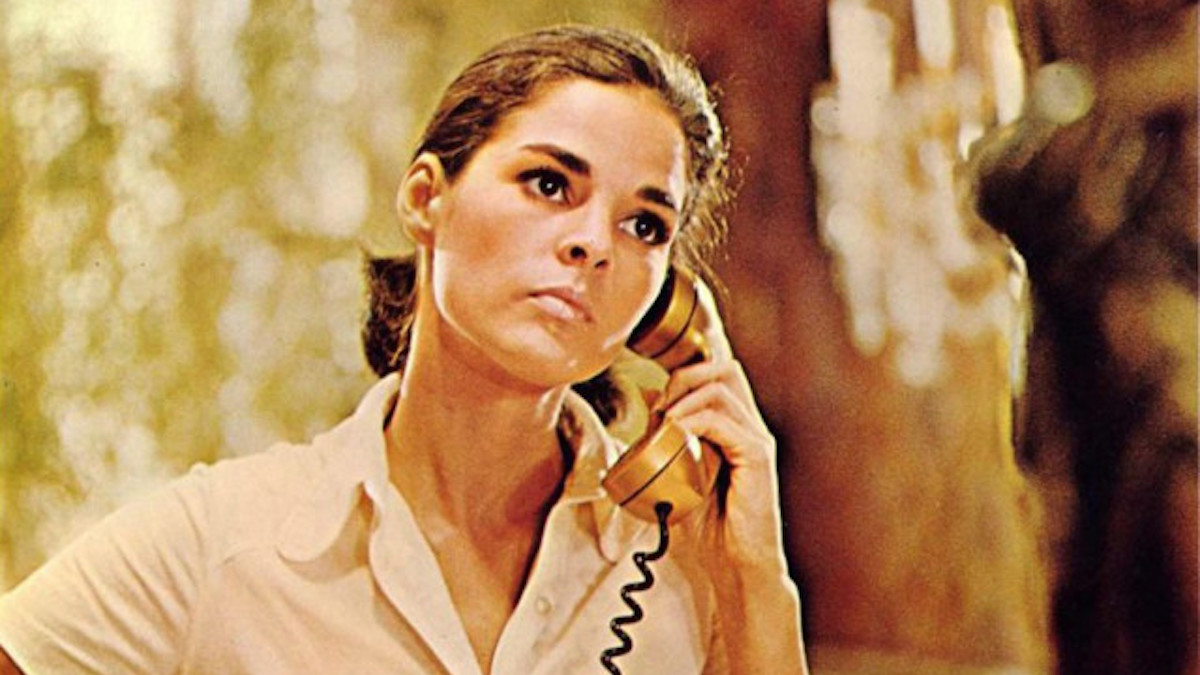

Adam Lowes – GOODBYE, COLUMBUS

A late-60s coming-of-age romantic comedy about a college-age Jewish kid trying to find his way in the world, adapted from a popular short novel from the same era. While this description could be entirely applied to The Graduate from two years earlier, this Philip Roth adaptation of his novella of the same name makes a fine companion piece to Mike Nichols’ zeitgeist-y smash hit, and is one of those near-classics which has somehow failed to find longevity. Featuring a winning central performance from the great Richard Benjamin – who went on to a solid directorial career a decade or so later – it’s a humorous satire on the class divide in 60s America, and in many way, it’s a more perceptive and enjoyable film than the misadventures of Benjamin Braddock. With a fanatic score and title track by Californian pop group The Association, Goodbye, Columbus was a sizable hit for Paramount in that year, and I heartily recommend to those who have not seen it.

John Bleasdale – THE WILD BUNCH

The classical western had sustained a reinvention from without, with Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns giving us greedy amoral gunfighters, happy to gun people down in cold blood. 1969 would see his Once Upon A Time In The West sing a death mass over the genre, but it was Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch which blew bloody great holes in it … in slow motion … with a Gatling gun. Following a deadly bank robbery turned ambush, William Holden leads his band of aging outlaws over the southern border, pursued by bounty hunters led by an old member of the gang. There’ll be more robberies, betrayal and death before a final scene that had a young Martin Scorsese staggering from the theatre, as if from a ‘fever dream’. John Wayne blamed the film for killing of the Western and it’s easy to see why. But in reality the West is defined by the fact it’s always ending and that is what makes The Wild Bunch actually a classic Western. That ending is as shocking today as it ever was, even though it’s been copied countless times. Represents a nihilistic urge to go out in a blaze of glory, it goes to the dark heart of the Western.

Leave a Comment