Martin Scorsese has clearly cornered the market when it comes to the Irish mob flick, but that isn’t to say other filmmakers have also crafted some pretty compelling work within the same milieu, be it Ben Affleck’s return to his home turf of Boston for his second film as director – and arguably his best – with The Town, or Phil Joanou’s 1990 trip to Hell’s Kitchen in State of Grace. The latter is a film which has its ardent admirers despite being culturally eclipsed at the time of release, ironically owing to Goodfellas being out in cinemas in the same week, and considerably dwarfing State of Grace’s minuscule final $1.9m box office tally.

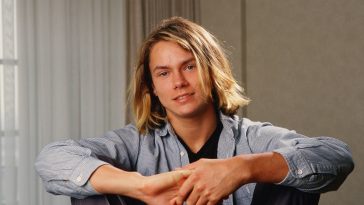

While it would be fair to say Joanou’s film isn’t in the same league of Scorsese’s masterwork, State of Grace still has a lot going for it, not least the then major casting coup of double-hitters Sean Penn and Gary Oldman, the hottest actors of that age back then. Joanou was still a fledging filmmaker, having cut his teeth on the darkly comic teen drama Three O’Clock High and the U2 rockumentary Rattle and Hum – the band’s song Trip Through Your Wires crops up on the film’s soundtrack. And on that subject, Joanou also managed to tap the maestro Ennio Morricone to score his feature. Add to this a fine array of supporting actors – including a young John C. Reilly making an early screen appearance – and the oft-used ‘cult classic’ is entirely justified here.

For the uninitiated, Penn is Irish-American cop Terry Noonan who ventures back to his childhood haunt undercover in an attempt to bring down the Irish crime organisation run by the formidable Frank Flannery (Ed Harris). But this is far from an easy task for the young officer, as Frank’s baby brother Jackie (Oldman) – a frequently sozzled and unpredictable livewire also runs with the crew – is Noonan’s best friend from childhood and Jackie’s sister Kathleen (Robin Wright) is his first love. Before you can say ‘conflict of interest’ Noonan has rekindled his relationship with Kathleen and bonded with Jackie, much to the annoyance of his boss (played by John Turturro). To make matters worse, Jackie’s hot-headed, bordering on psychotic behaviour leads to tensions amongst rival mobs, making Noonan’s objectives even harder.

Ok, so it’s familiar pulpy fare all round – some would argue bordering on cliché – yet Joanou shows real reverence for the material. Only in his late twenties himself at this point, he directs with the kind of passion and verve you’d expect from a younger director eager to make his impression in the industry. That Joanou’s career didn’t quite take off in the same way some of his nineties directing peers did – his biggest subsequent hit was the 1992 melodrama Final Analysis – is something of a shame. He’s really adept at staging some fantastic set-pieces, one of which see’s Noonan and Jackie breathlessly hightail it out of a burning building they’ve torched. Another standout scene see’s the tension ratcheted up to almost unbearable levels – aided by Morricone’s score – as rival gangs teeter on the brink of a large shoot-out.

What is ultimately behind State of Grace’s enduring appeal is the two combustible leads. Penn is as intense and committed as you’d imagine, particularly as his guilt-ridden boozing starts to take a hold. Similarly, Oldman – in one of his earliest State-side roles – is magnetic, tearing up the screen whenever he lurches into shot. Like many nineties Oldman roles, he occasionally walks that thin tightrope between a more restrained deliver and the ostentatious, but he’s never less than compelling throughout, even at his most unpleasant. Even the film’s final Peckinpah-esque pub showdown does fall into the hackneyed device of being interwoven with the St. Patrick’s Day parade happening at the same time outside, it’s doesn’t distract from the rousing portrayal of the loyalty between friendship and kin which precedes it.

Leave a Comment