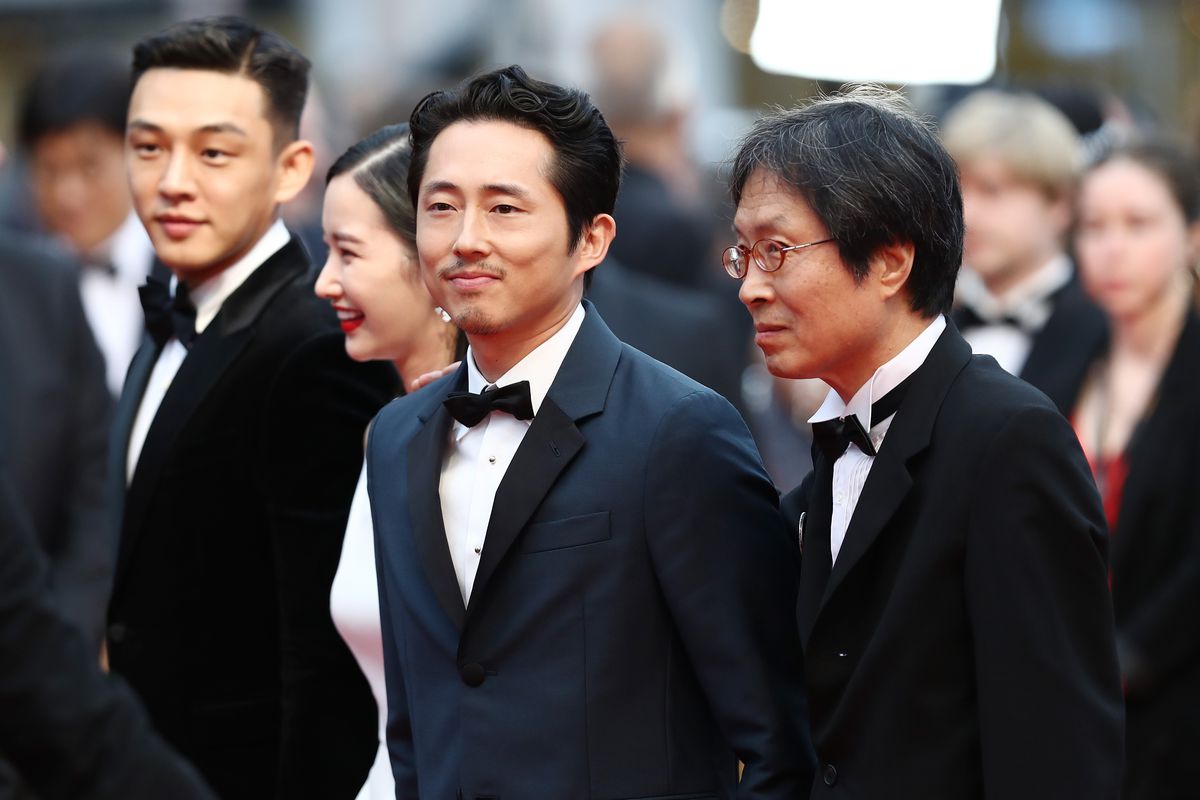

During the London Film Festival, we had the great pleasure of sitting down with Steven Yeun, one of the leads in the wondrous drama Burning, which is released in cinemas across the UK on February 1st. The American-Asian actor tells us what compelled him to head to Korea to shoot a movie and what it was like being on set with a hero, in the form of director Lee Chang-dong. He also discusses the ambiguity of the narrative, the themes of toxic masculinity and on the under-representation of Asians in Hollywood, and why, after the huge success of Crazy Rich Asians, it’s time the studios started investing more so in people from different cultures.

We’re meeting you during the festival circuit for this film, as you’ve been travelling the world with Burning. Have you found that different countries have reacted to the movie?

Absolutely. What’s been nice about this film coming from director Lee’s mind is that he always had a universal approach to the humanness of all of us and his films, to me, have always reflected back in that way. I’ve seen not too different of takes from each country that gets to watch this.

One thing that is consistent, is the acclaim – did you get a sense from reading the screenplay that you were signing up to something quite special?

For me, I didn’t really think of it to that extent. I just wanted to work with director Lee because he’s to me he’s one of the greatest film directors of the modern age.

You’ve said you wanted to work with him because he’s one of your heroes – so what is it about his work you admire so much?

The thing I’ve been very fortunate with is that I’ve been able to work with voices that are very direct and sure in their perspective of how the view things. Director Bong [Joon-ho] being one of them, and Boots Riley definitely being one of them., and director Lee being one of those people. You can see in their work that they have an uncompromising take on how they want to approach their films. The thing that really resonated for me with director Lee’s films was the first time I saw Poetry. I watched it and I saw my grandmother, and I saw a deep connection to the pain I must have put my own grandmother through when I was a kid. And then you go back to his filmography and you watch something like Peppermint Candy, and as a Korean immigrant to America, you always have these cultural feelings within yourself that you can’t explain. It’s kind of like that unrequited Korean rage that a lot of men and women feel, Mostly from being on occupied territory for so much time, you know you can’t explain it because your parents don’t even have the words to explain it to you, nor are they really concerned about that at the moment because they’re just trying to survive in a new country. So, you grow up like this and you’re like, ‘Why am I me? What’s going on?’ And then you watch something like Peppermint Candy and you’re like, ‘Wow, that’s why I’m me. That makes total sense.’ For a film to speak like that to me was very important. It allows me to really understand the scope and ability of what filmmaking can do. So, I was like, if I get to work with director Lee, awesome. But I never thought that would happen.

There seemed to be a lot of unspoken, suggested drama between the characters; what they weren’t saying as well as what was in the dialogue.

Absolutely, and the film at the end, and the core of what it’s saying, is mostly said with what it doesn’t say.

Is that something you picked up on when you first read the script?

I would be lying if I said I connected every single dot as soon as I read it, but I had a really strong connection to the core of what it was going for, the character, the place this person was in, the potential existential angst he is feeling and also the emptiness inside him that kind of pervades. I felt like I understood that when I read the script for the first time. It’s hard to talk about this film because the questions are always going to be rooted in something concrete, but the whole film is about how life is not as concrete as we thought it was. So I apologise for my vague answers.

How was it getting into the head of such a vague character, so open to interpretation?

On a page it looks very different to how it does on the screen, on the page we hadn’t shown those choices yet, on the page it’s mostly just what happens and what people say. I had a deep connection to the character after reading the short story . That’s what Director Lee and I talked about a lot when we met; building him from a philosophical perspective. Not who or what he is but how he is looking at the world. The ambiguity kind of comes together at the end of the process.

You’ve mentioned what a big fan of Lee were you were before this. When on set were you still a fan or do you have to put that to one side and just treat him as your filmmaker?

I’m still a fan, but he just allowed me to break down any social barriers and really see him as a human being, and I think that was really wonderful to me—to be able to see someone I aspire to be like in that way. To be at his age and to have relinquished his ego as many times as he’s done over the course of his life, and to continue to do it, to make a film about the young generation without telling them what they are but rather empathising with who they are. That’s a really gracious way to approach film, and I think those are the things that you see and witness in people that you admire, and you think, ‘man, I hope I can do it like that, too.’ Yeah, it was a really wonderful and complete experience.

You’ve said that the film holds up a mirror to toxic masculinity – can you expand on that?

I think Ben, in some ways, is actually not a victim of toxic masculinity to some extent, depending on what he’s done, and that’s left up to interpretation. In some ways, Ben feels free to embrace his femininity; he feels that free, which is why he can move about so carefree in that way. He’s not encumbered by social rules or social stigmas based on certain things and ways that we have to be. He could show up in a dress for all he cares; I feel like he could. That kind of stuff doesn’t bother him. Now, that doesn’t mean he’s not flawed in his own ways, but I never saw toxic masculinity as necessarily representative within Ben. I actually saw it mostly in Jong-Su, where this is a man who is trying so hard to control his life but each step of the way, none of his decisions are his. They’re always up against everyone’s expectations of what he’s supposed to do. He’s so awkward in every exchange because he’s not free to just be the way he is. That’s applicable to everyone, regardless of whether you’re male or female, but I think in this particular sense, you can look at Jong-Su and go, ‘What drives a man to do the things that he does? What type of hurt and what type of boxes is this man trapped in, that he can’t feel free to embrace every aspect of him?’ And I think that’s the conversation that we’re having around toxic masculinity. What are the expectations that are placed on men to be like that we see as powerful? But in the end it only becomes its own trap, because it’s made for an archetype of a hulking man which is really just there for whoever looks like that, or can have a body like that, or is that person, and that’s not every single man, and for people to assume that’s less manly is really the trap that we found ourselves in. We’re trying to attain something that is not natural to everybody, and that’s not what a man is. A man is who are and your comfort level being that. So yeah, I think you definitely look at that and you go ‘Wow, Jong-su is flawed for sure.’ Ben is flawed, too, but we’re not entirely sure how.

Though flawed, there are aspects of his personality that are desirable, Do you find as an actor, even inadvertently, you adopt traits of the characters you’ve played across the course of your career?

Sure, yeah. If someone was to interview me while I was playing Ben, I don’t think I would have given a very fun interview. Not that I am doing one now! I think during that time, I was really in it. I think you carry with you the lessons that you’ve learned. For me, the lesson I learned from Ben that I continue to learn isn’t necessarily his carefree attitude, but is maybe just that his acceptance of himself. Just being comfortable within one’s skin. People go through their own journeys, however that manifests is different for each person.

It was difficult to tell when Ben was lying or not, most of the time. Were there truths to the character that you knew that the audience will never be aware of?

Director Lee was really wonderful and he gave me that freedom. I’m the only one who knows, and it defeats the purpose for me to say anything because that’s a choice I made for myself, and that’s my experience with the film. We come to all these conclusions, make decisions and say “this is what this is, based on this, this, this and this”, but then you peal it back you realise there is no actual evidence that anything went down. It’s all just conjecture and how pieces have been put together for you. So yeah, what’s real?

The film is enriched by its ambiguity, like for example, what Ben does for a living. When on set did you give him a job yourself?

Yeah, We talked about some things. I don’t want these answers that I give to be like, ‘This is what and who he is.’ But you know, maybe his money comes from real estate? If you look throughout his house, he has a lot of architecture books and sculptures and dioramas of early-stage buildings. So, director Lee and I would sometimes talk and be like, ‘Maybe he does that… or maybe he doesn’t!’ I made decisions for myself, but really, we were just serving the narrative of, ‘Life is a mystery.’

Even though the character has secrets from the audience – does he have any secrets from you as well?

I don’t think he has secrets from me. I think I made those decisions for myself to fully realise the character for myself in order to inhabit him. But ultimately, he’s not a man that’s certainly supposed to be known, so… sorry [laughs]

So while your career has taken place in America, you’ve now made a fully Korean movie – can you talk about that a little bit?

Yeah, I know that parameters-wise, how we’re going to digest it is that there’s a whole other market in Korea that you can really participate in, and I recognise that and that’s definitely true. I feel like I’ve gotten many opportunities in the past to participate in it in a different capacity and I didn’t take them. Not because of anything except that they didn’t feel natural to me, but this one did. I look at this as not the only thing that I’ll ever do in Korea, but, right now, the only one that really made sense for me to do. So, I look at it independent of where it’s being filmed and what culture that it’s being filmed in. Obviously that’s very important, but I look at it like I got the chance to be in an auteur’s movie, transcendent of any boundaries or barriers. His films are wonderfully universal; that’s what drew me in too. What I meant by being prepared to say ‘no’ to director Lee was that I didn’t want to service a Korean story that was so intrinsically about being Korean to the point that if I was in it, it would actually read false. Which now, in hindsight, knowing director Lee, he would never let that happen anyway, he would just not cast me. But this story very much felt universal in that way, almost like we were making this on the moon, you know? In its own vacuum. I look at it as a hope, as our world does become more connected and cosmopolitan, that we can just skip over ponds and just make movies with other people if we want to. I will say that it’s hard; it’s not going to be so easy. I think this one was really kismet in that way, to find a moment in time where America has built up enough Asian-Americans’ careers that they could even be considered people that have jobs in Hollywood, and then go and do something in Korea and have the actor be able to speak Korean. Those are things that we’ve tried but we never got all the pieces together. I feel fortunate that I get to be part of this one because I feel that it’s kind of a freak situation.

As an Asian-American, we’ve seen this year with Crazy Rich Asians, which was a revelation in the box office, that it’s got a point now with studios, it’s no longer a risk to have films with people of colour in the lead, but a necessity? They’re making enough money to prove that you don’t need white America protagonists for films to do well.

Well you realise the disconnect between what people are willing to go with, what they’re living with every day, and what businesses were telling them life was. I think that’s what is really great about what’s happened with Black Panther and Crazy Rich Asians. They might not have played the game of perfect one-to-one representations of Asian people or black America, but what it has done is it’s said to the studios that your money issue doesn’t make sense anymore. If you want to use the whole ‘People don’t bring in money if you’re not white’ argument, well, it doesn’t function, so now what? Let’s just make the movies then. I think that’s really cool. I think that’s part of the process that I’m really interested in, what comes after. Is there more green-lighting of eclectic tales of different people’s lives, regardless of skin colour? Because I think that’s ultimately where everyone wants to get to, humanness, and to feel human. I think every day in our own ecosystems, whether they’re eclectic or not, if they are, you’re usually made aware that everyone is just living their own lives and trying to get by like a human being. But there are these extra things that we have to deal with that we just made up for ourselves. So yeah, I’m excited. I mean I don’t own a studio, so I don’t know what’s gonna happen.

When you were growing up, did you feel under-represented in cinema?

When I was young my hero was Will Smith. That’s because he was probably the closest to my own personal journey, of feeling ‘other’ or ‘outsider.’ Fresh Prince was exactly that. Then, you try to connect to mainstream stuff, and it’s not to say I can’t connect to a film that has a white protagonist, like of course I can, we’re all human beings, those things spoke to me. But sometimes, having a more nuanced approach to how it can connect to you is really that much more important. Watching Peppermint Candy was massive for me. Massive. To know that I could go to a place where someone looks like me, feels like me, and has the emotions that I would run through in that scenario was a real wonderful message of not feeling alone. I think we’re getting to that. We’ll see how it all shakes down.

The film has an intriguing love triangle at its core, and I’ve never seen it explored quite like this before…

It was a love triangle that wasn’t necessarily overly burdensome on the connection, per se. It was more three people that were all alone in their own respective ways, that were trying to find meaning in their own lives by finding something. I heard this really great film critic say it like this, and I thought that it was really wonderful and that’s how I felt: It was as if each character was waiting for the other. So Hae-mi (Jong-seo Jun) was waiting for Ben her whole life, Ben was waiting for Jong-su, and Jong-su was waiting for Hae-mi—something to complete them. Or to take them away, whatever that means, you know; they were all burning for something or someone to interject in their life trajectory. We saw it manifest and culminate in these three people. Yeah, it was interesting. It was almost like, not a triangle, but a singular dot. They were all kind of the same person in some way. That’s what I’ve heard a lot too, that people walk away from this film like, ‘I feel like I’m all three of them,’ and I’m like, ‘Yeah, we are!.

My favourite scene was when Hae-mi dances. How was that to shoot? It’s beautiful to watch back, could you get a sense for that when it was taking place?

Actually we did, because we played that song out of the Porsche, and Jong-seo was incredible. It was magic hour. We had set away two weeks to shoot at magic hour every day, so we’d get there, prep for like four hours and just shoot for 45 minutes and then we’d be done. She was brilliant; I think it only took about three takes. When we shot that, we were like… ‘Oh shit we did it! That was incredible’ I remember that; I remember us going to the monitors and being like that is one of the most beautiful things that we’ve shot. She’s amazing.

Leave a Comment