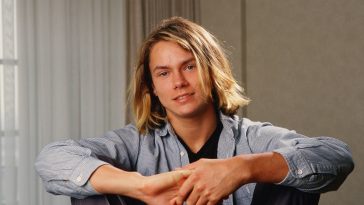

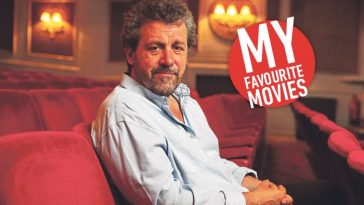

You’d be hard-pressed to find a more raw and honest autobiographical piece of filmmaking, than that of which we’re seeing in Farming. Telling a story about a young Nigerian child who is ‘farmed’ to a working class white family, we watch on as he struggles with a sense of identity, becoming the figurehead of a local group of racist skinheads. The story is based on the very experiences of writer/director Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje, and we had the pleasure of sitting down with him, alongside the film’s leading star Damson Idris, to discuss the challenging themes that are tackled in this affecting piece of cinema.

I’d never heard of Farming until I saw this movie, which feels wrong having been born and raised here in London. Is that partly what compelled you to tell this story, to not just put your own experiences out there, but to let people know about something that should be taught and talked about?

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: Definitely. This is a very important part of British history, a practise that shaped the way Britain has become. The children that were farmed essentially became the first black British generation to be born here, and so it had an indelible impact on how society was shaped. You’d be forgiven for not being aware of the phenomenon because the Nigerian immigrants normally fostered their children out to white working class families below the radar where questions and checks and balances weren’t really put in place, which is probably one of the reasons it didn’t come to the public notice. But definitely that was, apart from the personal, cathartic reason to share my experience, we’re very much aware as black Britons of the American black struggle, in fact more so than our own. Even the West Indian journey in the Windrush, but nothing is ever said of the African migration to Britain, and this not only gives us an identity in Britain but it validates our experience and our parents generation, I do think it should become a part of the curriculum because it’s an important part of British history.

I do know so much about race and prejudice in America, and yet so little about what has happened on my own doorstep.

Damson Idris: It’s swept under the carpet and there haven’t been a lot of avenues to tell it. Art is such a big factor in America, through music and movies, even actual art, but we just tend to not have it here, so this movie is beautiful for that and I hope it inspires more people to write stories of their own and not have to wait 20 years like Adewale had to.

Yeah we speak so frequently about how we’re moving forward as an industry and diversifying and giving a platform to filmmakers who aren’t white, but what is the reality of that? What was it like making a movie as a first-time black filmmaker, and telling a story about race?

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: It was hell, to be honest, I’m not going to sugar coat it. But you know, look, obviously there are pitfalls like the fact I’m a first-time filmmaker, I’m an actor making a transition to become a director, and I’m a black actor. It was so difficult to get people to take me seriously, and they wanted to take the script off of me and rewrite it, dilute it and there were many different renditions. But I knew my vision. I thought it was really important for this story to have a black perspective, because I’ve seen stories told about the black experience, but from a white perspective, and I’ve never really connected to it. I wanted to show a Britain that I grew up with. The Americans are always talking about tea and crumpets or The Beatles, but they have no idea that there is a whole other world that exists within Britain and it was important for me that it was myself telling that story, as a black resident, and show what life was like. So it was extremely tough, and the fact that the diversity chapter has come forth and it’s the perfect time for a film like this to come to fruition is great, but you know, it was not always the case back then and it’s been very tough. To be quite honest, financially this film was not supported by the industry, not by Film4 or BFI, the BBC. I got the money from foreign investors, whether it was America or France, which again, this is a British story you would think that would want to represent it.

Damson Idris: I put in a couple million [laughs]

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: But that’s also a telling factor, spouting the rhetoric of how we support black filmmakers, but you’ve got to put your money where your mouth is, and that didn’t happen in this case.

You’ve mentioned it was a cathartic experience putting your story onto screen – but at the same time, did you have any apprehensions? This is a chapter in your life that I would assume you don’t look back on fondly, so it takes a lot of courage to bring this story to people and say ‘this is what I did, this is what I went through’. So even though it was important to bring this onto screen, were there times during the process where you had to question whether you were fully comfortable with people knowing about this side of your history?

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: Absolutely. I thought about how much of the truth I wanted to tell, how much I wanted to indict myself, how much I wanted to indict my parents, and each time I questioned myself, it was always because the ends justified the means. The healing process that would come out of it both for myself and my family who went through it, that was the key factor, and every time I asked myself the question it was like, absolutely. But as a human individual, absolutely I was at points afraid of saying certain things about what I’d been through, but ultimately it’s the truth that is going to set me free, and the project was born out of a need to be free of it. You can’t half step that, it has to be the whole truth or nothing, and that’s why it was a huge sense of accomplishment, and gratification having gone through that process, because what’s happened is I’ve not only told my story, there’s been a huge outpouring, it has become the voice of a generation of people that went through it, and that again gave it validation.

So you feel free of it now? Has something been lifted?

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: Absolutely. There was a point in the screenings when I would sit in there and watch it, but now I don’t feel the need to do that anymore, I don’t feel the need to torture myself. I’m ready to move forward into a new place in my life, so absolutely.

In regards to the character, was it always a character on a page in a story Damson? Or were you playing a version of Adewale? So say you wanted to know how he was feeling in a certain moment, would you ask your director how he felt back then, or try to access it as though a fictional creation?

Damson Idris: Half and half, actually. When we first started it was fictional, but during the rehearsal process we sat down and had full on conversations about his experiences, and it’s actually the stuff that wasn’t on the page that really drew me to know exactly how he’d feel in a moment. So it was reality based anyway.

And when directing did you direct the role as being a version of yourself or did you have to have a disconnect between who you were and the character in the movie?

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: It’s interesting because coming at is an actor as well as a director, I always respected the actor. Part of it was that I knew I’d made the right choice and I had to respect the fact I’d made the right choice, so the script in many ways was a platform, and if I created the space and informed my actor, I could trust that he could go there. There were conversations myself and Damson had about his own past which we would access to take him to a certain place. But yes there were instances where I said ‘this is how I felt at this moment’, and we both had to relive it together.

Damson Idris: He’d start by saying, ‘in reality what happened…’ quietly to me. But you know to walk in his shoes was truly a blessing because not only do I have admiration for Adewale and his career, but also that journey, from where he came from to the man he is now, seeing that on the screen is something that is going to inspire so many young people, regardless of the places they’re in and the situations they’re in, they will be able to understand that if he went through that, then this is nothing, I can pull through this.

There are some scenes that are so difficult to watch from a viewer’s point of view, and I was wondering if there were any in particular that were really hard to direct, and really hard to perform?

Damson Idris: My hardest scene to perform, which is actually shocking because there were tougher scenes to watch I’m sure, was the suicide scene. I remember that day, I felt like I was going, you know? I was at the top of the scrapyard and before we started we both had a chokey moment, then he left and we did it, and I remember going home and crying my eyes out for the rest of the night. I can’t remember where in the shoot that was, or what we had to do after. Was it the last day?

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: Um, no, it wasn’t the last day, but I remember it vividly.

Damson Idris: Same. It was the toughest scene for me. It wasn’t actually the hanging, it was preparing myself to make the decision to do it. In that moment I understood exactly where this boy was coming from, I understood exactly that this decision was the only place he felt safe, and I was able to then identify and empathise with the many other teenagers who have done that, and why they’ve got to this place where they feel that only in death will they be set free, and it’s the lack of love.

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: Yeah, I think that’s the same scene for me as well. Climbing to the top of that scrapheap. The whole production team were like ‘wow this is such a beautiful scene’ and I’m like, look, this is my life. I had to impart upon Damson what death meant to me, what suicide meant at that moment, and it didn’t mean death to me it meant freedom. It was the only way I could conceivably stop the pain and the hurt. I also whispered to Damson some of his own past that we accessed, and that combination meant we were both… you know.

Damson Idris: It’s crazy because as an actor you still have to get stuff right. You have to get the lighting right, the sound, the cameras, and I was ready to go, I was about to do it without the cameras rolling! I was living it. There were many moments like that but that was the biggest for me.

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: And you can see it on the screen.

Damson Idris: It’s the scene I can’t watch. I turn away every time.

Adewale Akinnouye-Agbaje: He has barely 12 words to say in the whole movie, it’s all emotive, you know? And if you watch his face when he does that, the range of emotions, it’s so compelling, it brings me to tears just watching it.

Leave a Comment